Words: 1079 | Estimated Reading Time: 6 minutes | Views: 6487

Recently, an aging apartment building in Itabashi Ward, Tokyo—more than 40 years old—became the focus of public attention. Ownership of the building changed earlier this year to a company represented by a legally registered Chinese corporate representative, and shortly thereafter residents received notices stating that, from August, rents would be raised sharply to 260%–320% of the current level. For a unit of around 30 square meters, monthly rent would surge from ¥72,500 to ¥190,000, vastly exceeding market rates for comparable properties in the area. The sudden hike triggered a mass exodus: to date, about 40% of residents have chosen or decided to move out of the building.

What has further inflamed controversy is residents’ claims that the building was being used for short-term rentals without proper registration, with frequent turnover of occupants and serious noise disturbances. In addition, the building’s only elevator unexpectedly stopped functioning last month and repairs are expected to take as long as six months, severely affecting residents on upper floors, especially the elderly. The landlord’s representative declined to comment. The incident rapidly spread on Japanese social media and exposed multiple challenges Tokyo faces in regulating aging residences, the legality of short-term rentals, and rental relationship governance amid foreign capital participation.

Is running short-term rentals in Tokyo that profitable?

Yes — quite profitable. Especially when you operate an entire building.

In Japan, and particularly in Tokyo, operating short-term rentals can indeed offer attractive profits, especially when the entire building is operated as a unit. With the recovery of tourism and a weaker yen, the short-term rental market has seen robust growth.

According to data from the Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO), the number of inbound foreign visitors in July 2024 was about 3.2925 million, an increase of 10.1% compared with 2019 and more than 8 million more than the same period in 2023. This growth has directly driven surging demand for short-term rentals and sparked a wave of investment into the sector.

Gross yields above 10%

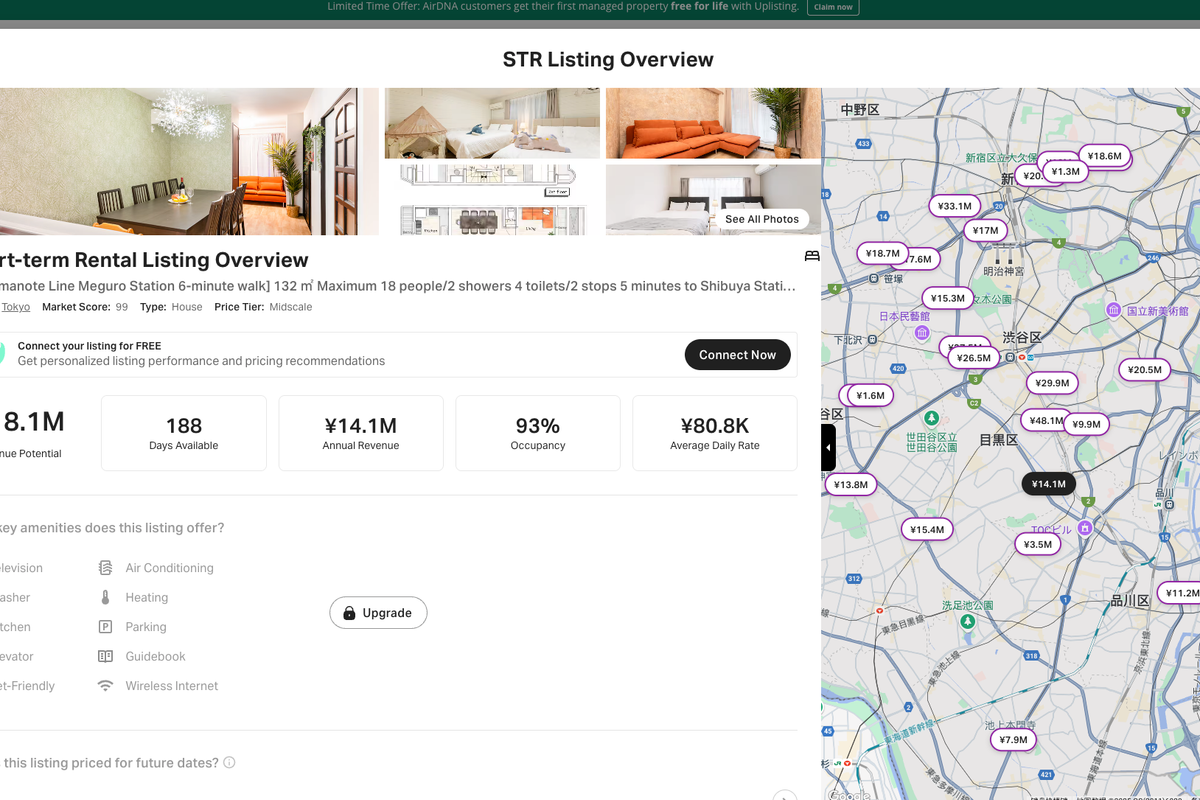

In terms of returns, short-term rentals typically deliver high yields. For example, consider the entire-building short-term rental in Meguro shown below: its estimated annual revenue ranges from ¥14.1–18.1 million.

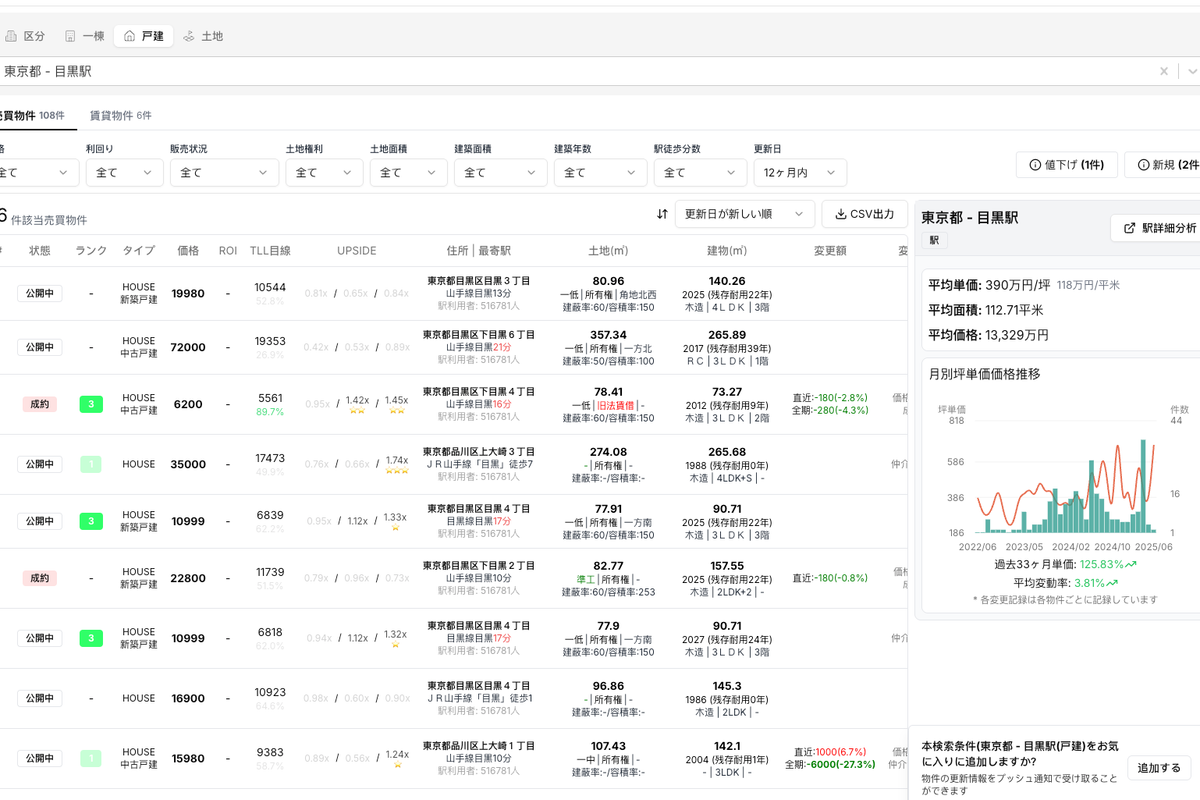

Using Urbalytics’ search function, you can see that detached houses in Meguro have unit prices of about ¥3.9 million per tsubo; a 100 sqm property is roughly ¥100–120 million. With annual revenue in the ¥14.1–18.1 million range, the gross yield can be about 12%–18%.

Even after deducting 20%–30% for operating expenses, net returns above 10% are not uncommon. Compared with similar whole-building income properties in the area that show gross yields of 3%–4%, it’s not hard to understand why some owners are willing to take risks.

In the entire-building income model described above, many operating expenses can be shared (for example, advertising and cleaning), reducing operating costs and improving actual profit margins. This dynamic also helps explain why some landlords resort to aggressive measures to “evict tenants.”

Is an "egregious rent increase" illegal? What can tenants do?

Raising rent is not illegal per se; however, an excessive, below-the-belt rent hike that far exceeds local averages is unlawful.

Act on Land and Building Leases, Article 32, Paragraph 1:

If the rent for a building becomes unreasonable compared with rents for similar nearby buildings because of an increase or decrease in taxes or other charges on the land or building, a rise or fall in the value of the land or building, or other changes in economic conditions, either party to the contract may request that the rent for the building be adjusted (increased or decreased) from the future, regardless of the terms previously agreed in the contract.

Under Article 32 of the Act on Land and Building Leases, a landlord may request a rent adjustment in specific circumstances, such as increased taxes, changes in economic conditions, or changes in rents for comparable nearby properties. However, any rent adjustment must be agreed to by the tenant; a landlord cannot unilaterally impose it. If the tenant objects, the landlord must file suit in court, and a judge will determine a fair level based on market conditions and reasonableness. Past judicial precedents show that courts typically find a compromise between the original rent and market rent. If the landlord’s proposed increase is clearly well above market levels, it is unlikely to be approved even if the case goes to court.

In practice, rent increase notices that are far above market levels are often not intended to genuinely raise rent but to induce tenants to vacate voluntarily—for example, if the landlord plans to redevelop the site or convert the property into short-term rentals. However, so long as a tenant clearly refuses the rent increase and indicates an intention to remain, the landlord generally cannot take stronger legal measures to force the tenant out.

How to respond to landlord "harassment"

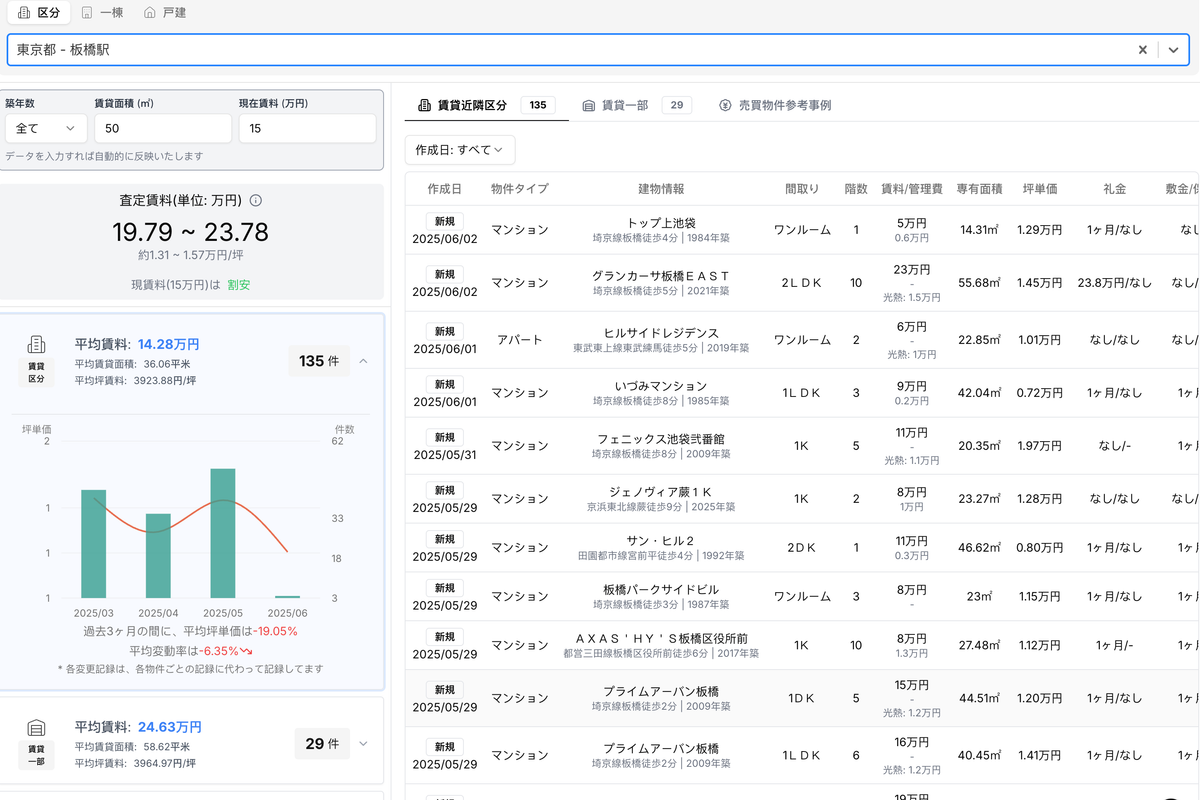

As an ordinary tenant, you can use tools like Suumo and Homes to check average rents in the area. Urbalytics also provides a rent search tool. By comparing published listings, you can contest an unreasonable rent increase.

In some cases, landlords may try to force tenants out by shutting down the elevator, turning off power in common areas, or similar tactics. While such actions may amount to "harassment," if the landlord claims they are due to equipment aging or necessary maintenance, it can be difficult for tenants to prove malicious intent. Nevertheless, if such actions seriously affect tenants’ quality of life, tenants can request an appropriate rent reduction. For example, courts have recognized rent reductions of around 10% when interior facilities become unusable, while problems with public facilities like elevators may justify a smaller reduction.

Even if you disagree with a rent increase, you should continue to pay rent on time at the original rate. If the landlord refuses to accept the rent, you can use the Legal Affairs Bureau’s deposit (kyōtaku) system to deposit the rent into escrow, thereby demonstrating that you have fulfilled your payment obligation and avoiding being deemed in breach of contract.

Conclusion

Tokyo’s short-term rental market shows strong profit potential against the backdrop of tourism recovery and inflows of foreign capital. However, an excessive pursuit of profit can strain tenant–landlord relations and even trigger social problems. For tenants, understanding their rights and responding appropriately to landlords’ rent-increase tactics is critical. For investors and policymakers, balancing profit motives with social responsibility to ensure a healthy rental market is an equally important challenge.

Copyright: This article is original content by the author. Please do not reproduce, copy, or quote without permission. For usage requests, please contact the author or this site.