Words: 1603 | Estimated Reading Time: 9 minutes | Views: 3401

Why large-scale redevelopment doesn’t always succeed — starting from Jujo’s “bright ruins”

In recent years, Tokyo has seen a vigorous wave of urban redevelopment. Driven by disaster-prevention needs and capital interest, more and more old neighborhoods are being replaced by high-rise towers and mixed-use complexes. However, urban renewal does not automatically mean urban revival. Without grounded realities and a user-centered perspective, even the grandest schemes can become cold, "bright ruins."

Today we examine a typical example — the Jujo Station redevelopment project, a large-scale mixed-use development combining residential, commercial, cultural and administrative functions, and how it lost vitality in less than a year.

Jujo redevelopment: from bustling to deserted

Jujo is a traditional neighborhood rich in Showa-era character. The famous Jujo Ginza shopping street, known for low prices and a friendly atmosphere, is regarded as one of Tokyo’s three major Ginzas. Precisely for this reason, when a redevelopment project launched under the banner of "disaster prevention" took shape, it was expected to symbolize a "living standards upgrade," but quickly revealed disappointing results.

In 2024, "The Tower Jujo" was completed. This 39-story residential tower sells units priced above JPY 100 million and was nicknamed the "100‑million‑yen condo" of Kita Ward. In addition to residences, it planned a commercial zone "J & Mall" featuring an upscale supermarket (Queen’s Isetan), chain restaurants, convenience stores, beauty salons, and a public cultural facility "Jectel" with a 3D printing studio, reading rooms and a multipurpose cultural space. It sounded flawless on paper, but reality was sobering.

In May 2025, our field visit found that this new mixed-use complex in a core location already had nearly half of its retail units vacant. In particular, the second-floor commercial zone had only five tenants and some areas were not even fitted out. Confusingly, the mall lacked an effective wayfinding system — most shop locations can’t be determined from the entrance, and there is not even an official website, creating significant friction for outside visitors.

Why would such a large project fall quiet in under a year?

Root causes: redevelopment designed apart from everyday life

#1 Rents priced far above the local market, detached from reality

Although J & Mall sits in front of Jujo Station with an excellent location and a brand-new building, its rent levels are clearly higher than those in the surrounding traditional commercial zone. For example, medical-use rents on the 1st floor reach about JPY 25,000–30,000 per tsubo, while a few hundred meters away in Jujo Ginza rents are only around JPY 14,000 per tsubo.

This "upmarket positioning"—without strong brands or steady foot traffic—deters local merchants. Many small shop owners who used to operate on Jujo’s west-side shopping street cannot afford such high fixed costs.

#2 Poor circulation design and a lack of basic wayfinding

The design also has notable flaws:

Entrances are narrow and the mall’s wayfinding is extremely unclear

The building lacks floor guides and ground-level navigation cannot accurately locate tenants

The mall’s official website is still not live, preventing pre-visit information checks

These issues make "not being able to find a shop" very common, reducing accessibility and attractiveness.

Especially problematic is that the anchor tenant, Queen’s Isetan, was placed on the 2nd floor, which violates the basic principle that a supermarket should be on the ground floor to serve as an anchor and draw traffic. Many visitors don’t even know where the supermarket is, so circulation and repeat visits don’t materialize.

#3 Tenant mix lacks magnetic brands and everyday-demand uses

Successful shopping areas typically place low-barrier, high-frequency uses at street level — coffee shops, light eateries, and specialty convenience retail — to generate steady foot traffic.

By contrast, J & Mall’s composition includes:

Real estate agencies, pawn/recycling shops, clinics, dry cleaners — uses that are purpose-driven but low in casual foot traffic

Primarily chain convenience stores and fast food with little distinctiveness

Few cafés, dessert shops, or bookstores that encourage lingering

This results in a predominantly functional rather than everyday-lifestyle atmosphere: it neither attracts outside visitors nor generates sufficient activity to activate consumption by residents upstairs.

#4 Building design sacrifices comfort and usability

Redevelopment should upgrade function and comfort, but J & Mall’s physical spaces suffer from multiple problems:

Several exterior areas are open to the elements, allowing rain to enter

Some zones lack adequate HVAC coverage, making them stuffy in summer and cold in winter

Lacks the all-weather adaptability of an enclosed shopping arcade

Compared with traditional arcade shopping streets, this project performs worse in terms of walkability and environmental control, lowering utilization.

This is not an isolated case: Azabudai Hills and Tokyu Plaza also cooled off

Jujo’s redevelopment difficulties are not unique. Several large Tokyo redevelopment projects in recent years have faced challenges during leasing or early operations.

#1 Tokyu Plaza Ginza

Tokyu Plaza Ginza was once an iconic commercial facility in Ginza, attracting many visitors with distinctive architecture and a prime location. However, in recent years it faced challenges such as high rents, a limited tenant mix, poor circulation design, and lagging digital transformation, which slowed customer acquisition. Operational shortcomings ultimately led to its acquisition by a Hong Kong private real estate firm in February 2025; the new owner plans a full redevelopment. Major renovations are scheduled for 2026 to reposition it as a "new concept retail center" better aligned with market demand.

#2 Omiya-mon Street

Omiya-mon Street is a redevelopment at the east exit of Omiya Station in Saitama Prefecture, built on the former Chuo Department Store site with a total investment of about JPY 65.8 billion, including JPY 49.1 billion in public funds. The project aimed to introduce a diverse range of commercial facilities to inject new energy and raise regional value. Despite the large investment, it failed to meet expectations due to:

A narrow tenant mix: the commercial zone became dominated by clinics and other medical services, lacking retail and dining that attract foot traffic, creating an atmosphere more like a mixed-use office building than a shopping district.

Uninspiring design: originally planned curves and glass elements were simplified during design, resulting in a bland facade that failed to draw customers.

Unclear operating strategy: the project lacked a defined market positioning and operational plan to attract target customers, resulting in insufficient foot traffic.

As of 2023 the commercial occupancy rate was only 66%, far below expectations. The project became a textbook case of inefficient use of public funds.

#3 Azabudai Hills

Azabudai Hills is a massive redevelopment in Minato Ward led by Mori Building, with total investment exceeding JPY 640 billion to create an integrated urban complex of offices, residences, retail and culture. Despite its scale, high rents and unclear commercial positioning left the project without a clear target customer; intense nearby competition and blurred differentiation caused slow tenant uptake — even two years after opening, less than half of the commercial and office spaces were occupied.

Investor takeaways

For real estate investors or companies looking to participate in urban renewal, the Jujo case offers several hard lessons:

1. Large development ≠ low risk

Don’t be dazzled by a redevelopment project’s scale or polish. Towers and full amenities do not guarantee operational success. Pay attention to actual leasing rates, the operator’s capability, and community acceptance — the backend data.

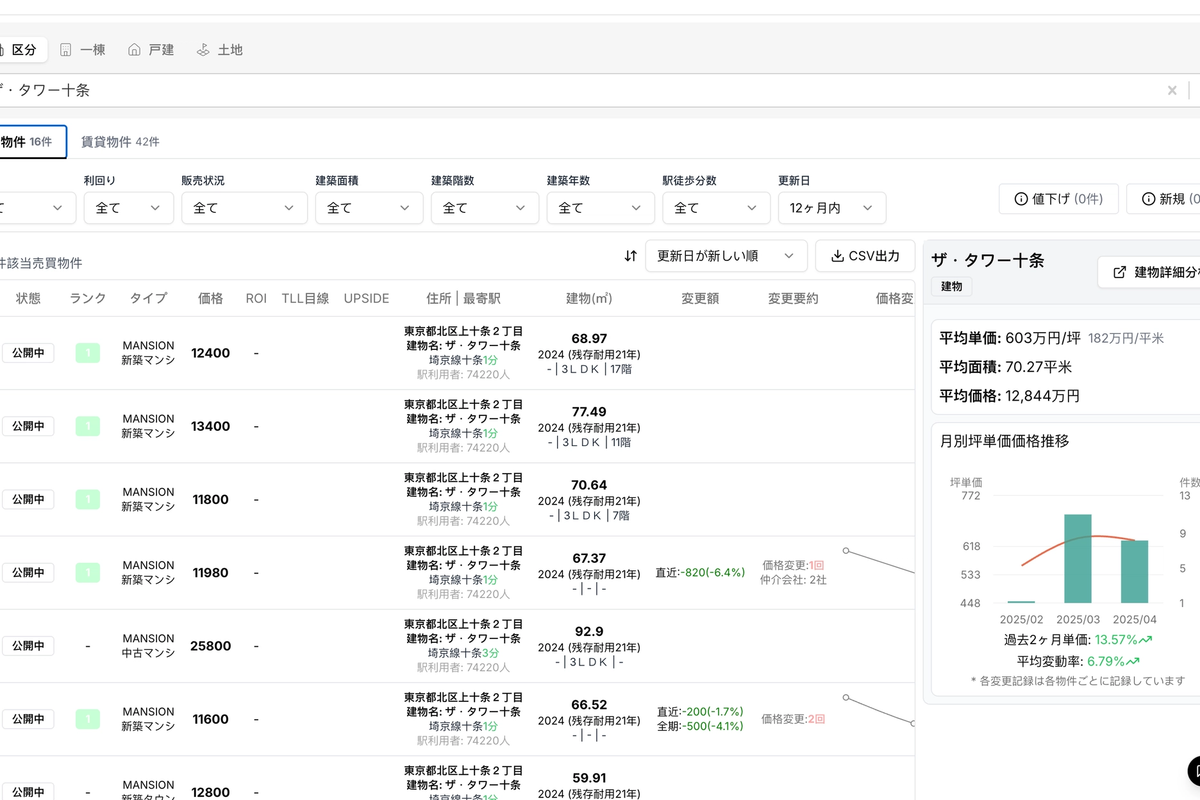

As shown on Urbalytics, The Tower Jujo’s average unit price is around JPY 6.03 million per tsubo, up from early‑2022 averages (JPY 4.5–5.5M), an increase of under 20%. Compared with price rises in areas like Tsukishima that nearly doubled, this is modest. Weak leasing after development has made the overall property less favorably perceived.

2. Watch for community rupture risks

Redevelopment often entails the disappearance of old communities. If the new development fails to accommodate existing living patterns and cultural structures, commercial activity will not follow. Successful redevelopment ensures the new embraces the old.

The Jujo station west‑exit redevelopment faced strong local opposition from the start. Jujo is known for its distinctive shitamachi character and dense wooden housing, and residents feel deeply attached to that traditional lifestyle. The proposed high‑rises and modern commercial facilities were seen by many as a threat to the neighborhood’s culture. Residents expressed opposition through organizing gatherings, submitting petitions, and filing administrative lawsuits. Although courts rejected these claims several times, the opposition drew public and media attention and prompted authorities to proceed more cautiously. For example, a project originally scheduled to begin in 2018 was delayed until 2021 due to resident pushback.

3. Operating capability can be more important than construction capability

Completing construction is only the beginning. Attracting and retaining brands, sustaining vitality, and continuously drawing visitors are the true tests of a project’s longevity. Does the developer have long‑term operating experience? Do they partner with local stakeholders? Investors should investigate these aspects thoroughly.

Even established developers like the Tokyu Group, with extensive development experience, have encountered operational challenges in projects across Ginza and Shibuya, which investors should note. Experienced developers must still adapt their operating strategies to rapidly changing market demands and consumer behavior to secure long‑term success.

Conclusion: "Being built" does not mean "being used"

Urban redevelopment is an irreversible trend, especially in Tokyo where disaster prevention, safety and renewal are priorities. But "being built" does not mean "being used." Jujo’s current state reminds us that a city exists for people, not for buildings.

Whether you are an investor, developer, or policymaker, before greenlighting the next redevelopment, consider one more question:

Who will genuinely want to come to — and stay in — this space?

Only by answering that can "redevelopment" truly become "re‑living."

Copyright: This article is original content by the author. Please do not reproduce, copy, or quote without permission. For usage requests, please contact the author or this site.