Words: 2293 | Estimated Reading Time: 12 minutes | Views: 1275

From "getting rich with other people's money" to "cash-flow deficits" — the final chapter of the high‑leverage era

The investment logic that once rapidly accumulated assets—"small down payment + high leverage + rent servicing debt"—has now completely failed under the combined impact of rising interest rates, tighter regulation, surging costs, and lowered capital gain expectations. The Bank of Japan has formally entered a rate‑hiking cycle; lending rates have generally risen to 2%–3.5%, while yields on centrally located investment properties are only 2%–3%. At the same time, maintenance costs, seismic standards, and repair expenses have jumped sharply, so the old strategy of snowballing wealth via low holding costs no longer works.

The Super‑Landlord (Super Oya‑san) Model

The "Super‑Landlord" (Super Oya‑san) model was a leverage‑based investment approach widely adopted during Japan's real estate boom from the 2000s through the mid‑2010s, primarily targeting salaried workers and middle‑class individuals.

The typical approach: investors purchased an entire apartment building (often low‑rise wooden or light‑steel construction) with an extremely low down payment or virtually "no money down," using very high bank loans (full or over loans), relying on rental income to cover repayments and generate asset appreciation.

Because Japan then operated in an ultra‑low interest environment, and because real estate agents, financial institutions, and guarantor companies often collaborated, many inexperienced or capital‑poor investors were nevertheless able to quickly "get on board" and become so‑called landlords (Oya‑san).

This model was once celebrated as a FIRE‑style path to "wealth with other people's money," and elevated to near‑mythical status. With low entry barriers (you could start with roughly JPY 3 million annual income), accommodating bank policies (major banks did over‑loans and underwriting was lax), and strong property price appreciation, it drew a large number of entrants.

Leading Figures and Success Stories

Shigeki Kanamori (金森重樹)

Works: 《1年で10億つくる!不動産投資の破壊的成功法》 (How to Build ¥1 Billion in One Year! — A Disruptive Approach to Real Estate Investing)

Profile: Used income‑capitalization methods to achieve whole‑building arbitrage and launched the “mail‑order landlord” project, training many "postal/remote" landlords.

Model: brokerage matchmaking → high‑leverage loans → whole‑building acquisition → entrusted management → positive cash flow.

Yūji Fujiyama (藤山勇司)

Works: 《年収300万円でも大家になれる》 (You Can Become a Landlord Even with Annual Income of ¥3 Million)

Known as an evangelist for enabling lower‑income people to become property investors.

Advocated starting with high‑yield small apartments in regional areas and quickly snowballing growth.

Takayuki Kimura (木村隆之)

Representative book: 《区分マンション投資で毎月20万円を得る!》 (Earn ¥200,000 Monthly from Sectional Apartment Investment!)

Although focused on sectional condominium units, he also promoted building loan‑backed "asset income pipelines."

Searching Amazon for "Super Oya" or "Salaryman Oya" returns many related book results. Many of these public figures have since established asset management or investment advisory firms and now, in a downturn, are pivoting to monetize eager novice investors trying to enter the market.

Increasing Defaults and Blow‑ups in Recent Years

In recent years the Super‑Landlord model has faced severe backlash in Japan as its underlying systemic fragility has been exposed, triggering a series of financial and social problems.

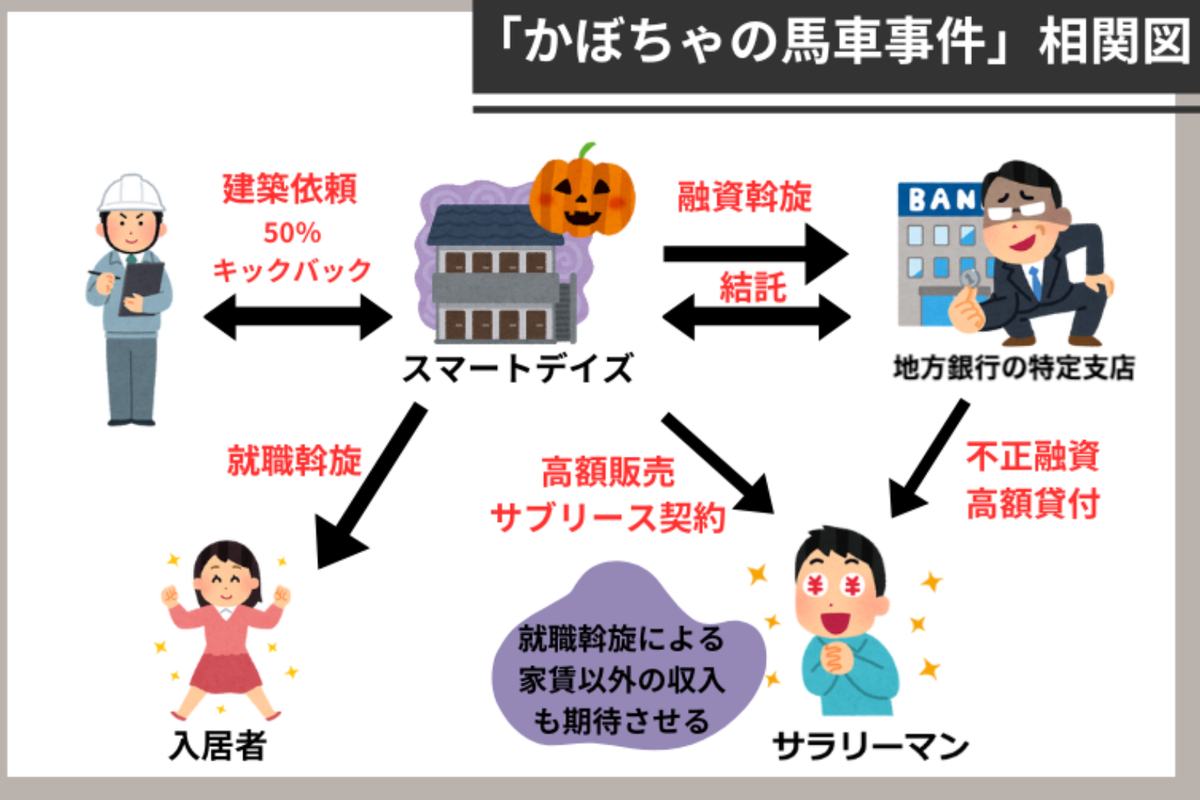

The most emblematic case is the 2018 "Suruga Bank Share House" scandal, where numerous investors—colluding with brokers and banks—obtained full loans using falsified income statements and rent projections to purchase the "Kabocha no Gensha" brand co‑living houses (Share Houses). Although they appeared to have stable rent income on paper, vacancy rates were high and rental receipts and operations collapsed, resulting in mass defaults, personal bankruptcies, and even suicides. The incident drew nationwide attention, prompted a Financial Services Agency investigation, and led to banks tightening personal investment loan approvals — marking the end of the golden age of high‑leverage whole‑building investments. Media reports have also documented many individual landlords forced to sell properties after the pandemic due to loan pressures and rising vacancies, confirming that the "small down payment, guaranteed profit" myth has long since collapsed. These cases transformed Super‑Landlords from investment icons into cautionary tales of financial accidents.

Major Recent Incidents

Collapse of the "Kabocha no Gensha" shared housing (2018): Operated by Smart Days (スマートデイズ), the female‑only shared housing project attracted many salaried investors who bought entire properties using high‑leverage loans from Suruga Bank (スルガ銀行). Due to poor operations, rental income could not cover loans, leaving investors in financial distress. After exposure, the Financial Services Agency investigated Suruga Bank for improper lending, and regulators tightened personal real estate loan policies nationwide.

TATERU falsified loan application scandal (2018): Proptech company TATERU was exposed for altering customers' bank deposit records without their knowledge to secure larger loans. The scandal caused the company's share price to plunge, damaged investor confidence, and led regulators to strengthen scrutiny of real estate loan application processes.

Leopalace21 construction violations (2019): Major developer Leopalace21 was found to have multiple apartment buildings that violated building standards for fire safety and soundproofing. The revelations forced many tenants to relocate, left investors facing asset devaluation and rental losses, and underscored the importance of rigorous building quality due diligence when acquiring properties.

It is notable that many of these blow‑ups were caused by developers themselves. These developers often cooperated with banks to provide favorable conditions to attract a certain investor profile.

Drivers of the Blow‑ups: The "One Property, One Company" Scheme

A once‑popular practice in Japanese real estate—especially during the Super‑Landlord era—was the "One Property, One Company" (一物件一会社スキーム) scheme.

The core of this scheme: for each acquired investment property, a separate corporate entity (typically a kabushiki kaisha) was established to hold that property. The structure was used to obscure the investor's true overall financial position and to continue rolling high‑LTV loans for further investments. Typical process:

Incorporation: The investor forms a new legal entity for each property, applying for loans and purchasing in the company's name.

Loan application: The new entity applies to banks for financing, with banks evaluating the company's balance sheet.

Property purchase: After loan approval, the entity acquires the target property in its name.

Rental operations: Rental income flows to the entity to service loans and cover operating costs.

Tax planning: Financial engineering within the entity is used for tax optimization, e.g., depreciation and expense allocation.

Attractions and perceived benefits

Loan flexibility: Each entity acts as an independent borrower and can apply separately for financing, avoiding individual credit limits.

Risk isolation: Operational and financial risks are confined to each entity, reducing consolidated portfolio exposure.

Tax optimization: Corporate entities can be arranged to achieve tax efficiencies.

However, after the Suruga blow‑up and with financial institutions tightening real estate lending scrutiny, banks have become more cautious about loans to newly formed entities. At the same time, credit bureaus such as CIC have strengthened data collection and information sharing, making it increasingly difficult to deceive lenders with a one‑property‑one‑company scheme.

2025 — The End of the Super‑Landlord Model

By 2025, Japan's real estate investment environment has changed fundamentally, making the Super‑Landlord model nearly unsustainable. Below is an overview of the main changes and their impacts:

#1 The Bank of Japan has formally entered a rate‑hiking cycle, with expectations of further increases

Since late 2024, after more than a decade of ultra‑loose policy, the Bank of Japan officially raised the policy rate to 0.25% and raised it again to 0.5% in Q1 2025. Although still low by global standards, this is a major shock for a real estate market long dependent on cheap leverage. Banks have simultaneously raised mortgage and investment property loan rates—regional banks in particular have lifted lending rates for investment properties to 2.0%–3.5%, substantially eroding investor cash flow. The previous Super‑Landlord strategy of using full loans and covering monthly payments with rent now risks producing negative cash flow (i.e., becoming cash‑flow negative landlords).

More critically, the market generally expects one to two further rate hikes between H2 2025 and 2026, and BOJ officials have indicated a return to "policy normalization." That implies investors face a long‑term interest rate environment higher than the past decade, compressing return expectations. Under these financial conditions, landlord models that rely on cheap leverage are effectively bankrupt as an approach; capital is more likely to flow into higher‑liquidity, lower‑operational‑cost assets, leaving the Super‑Landlord concept firmly rooted in the past.

According to recent simulations, the 10‑year floating mortgage rates show notable dispersion among major banks:

Lowest rate: SBI Sumishin Net Bank at 1.493%

Highest rate: Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation at 2.892%

Average across 12 banks: 2.142%

This compares with an average of 1.618% six months earlier, an overall increase of about 0.543%, and all banks have raised their projected rates. Although the policy rate rose by only 0.25%, banks have lifted long‑term rate expectations further, reflecting a consensus view that rates will continue to rise.

#2 Tightened financial policy and lending restrictions:

After the 2018 Suruga incident, regulators have tightened scrutiny of real estate lending. By 2025, banks have stricter policies for individual investors, requiring higher down payments and more rigorous income documentation, restricting the feasibility of high‑leverage investing. Currently, investment loan down payments generally require at least 30% (and often more), and typical salaried applicants are expected to demonstrate annual incomes of ¥7 million+. For applicants with stronger profiles at major banks, the threshold can be ¥10 million+, effectively blocking most ordinary individuals from entering the market or quickly replicating past strategies.

#3 Yield deterioration — "rent covering debt" is basically impossible:

Japan's population continues to decline, especially in regional cities where vacancy rates are rising and rental income is falling. At the same time, urban center property prices have risen, lowering investment returns and increasing investment risk.

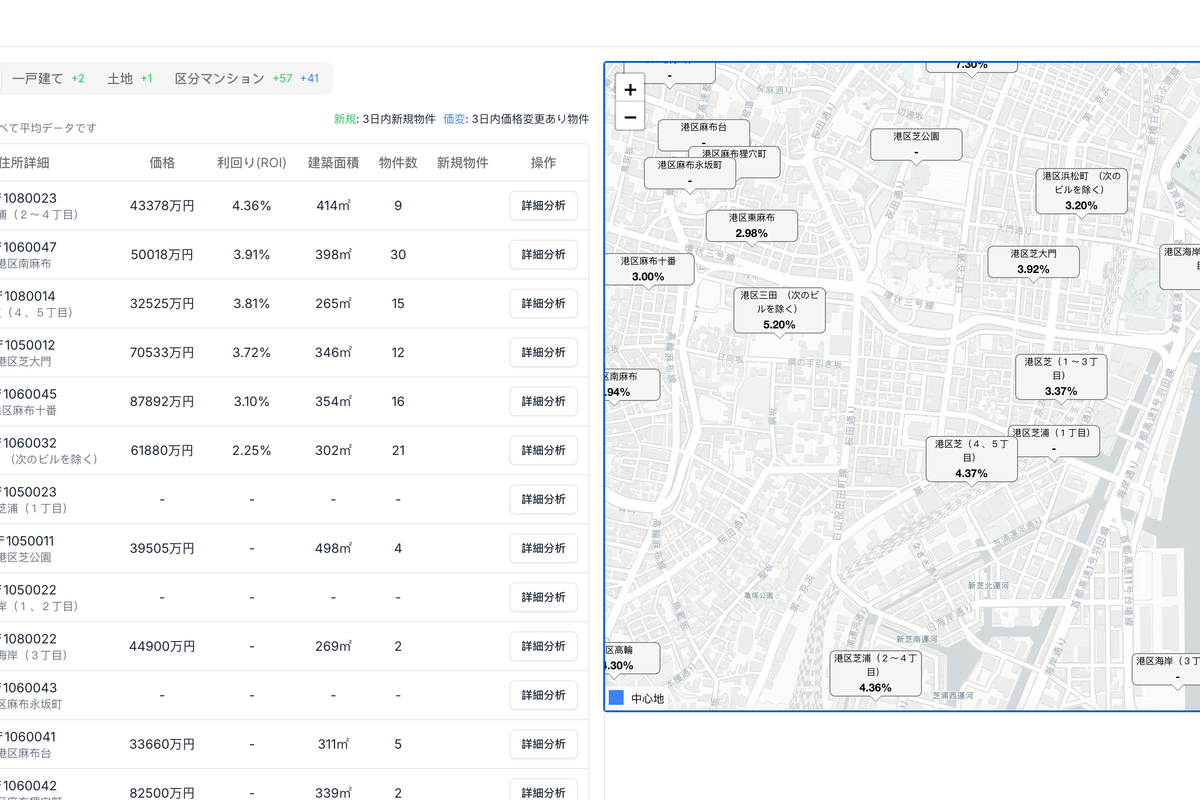

Urbalytics' operating yield maps show core area yields are now in the 2%–3% range, below mainstream target investment yields (3%+). Coupled with soaring maintenance costs, it's difficult to achieve break‑even unless assets appreciate substantially; snowballing scale expansion is no longer realistic.

#4 Rising building standards and maintenance costs:

Historically investors bought cheap, older wooden multi‑unit buildings and generated cash flow through light renovations. But with strengthened building regulations, particularly seismic and fire‑safety standards, many properties built before 1981 under the old seismic standard now fail to pass loan underwriting or resale unless structurally upgraded. For example, a seismic assessment required by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism can cost ¥300,000–¥500,000 per building, while structural reinforcement often runs ¥5–10 million or more. At the same time, costs for restoration and major repairs have risen by 30%–40% over the past five years. Roof waterproofing costs rose from an average of ¥6,000/m² in 2018 to ¥8,500/m² in 2024, and exterior wall refurbishments exceed ¥12,000/m². Labor costs have climbed sharply—daily rates in Tokyo increased from ¥18,000/day to over ¥25,000/day. These shifts mean the previous low‑maintenance, high‑cash‑flow snowball model now faces deteriorated cost, risk, and liquidity profiles.

#5 Steep decline in capital‑gain expectations:

Over the past decade, prices for investment properties in Tokyo and major ordinance‑designated cities surged—especially in popular districts such as Minato‑ku, waterfront areas, Fukuoka, and Osaka's Shinsaibashi—so prices for wooden one‑building properties generally rose by 30%–60% vs. 2015. For example, some 1K fully rented wooden properties in Tokyo saw per‑tsubo prices rise from ¥700,000 to over ¥1.5 million, while rental yields did not keep pace; even new buildings often show gross yields of only 4% or less. More investors believe prices have become disconnected from rental fundamentals, with limited upside and potential downside.

This high, consolidating price structure leads many investors to conclude: "buying now is taking the peak risk." With slower economic growth, rising rates, and reduced foreign capital inflows, the market widely expects limited further price appreciation, or even price corrections. Since capital gain prospects are weak and cash flow is shrinking under repair and tax pressures, the Super‑Landlord model is unsustainable.

Because of these converging factors, investor confidence in the real estate market has weakened. The once‑popular Super‑Landlord model is now regarded as too risky, and investors are migrating to more conservative strategies.

Advice for Investors in 2025

1. Avoid blindly chasing highs; shift to selecting "stable‑rent assets"

In a high‑rate environment, investment logic must shift from "capital‑gain driven" to "cash‑flow safety first." Prices in Tokyo and other tier‑one urban cores are at historical highs with limited upside; investors should focus on assets that:

have stable rental income (closely tied to local employment/transportation structures)

are medium‑sized properties that can be maintained at low cost

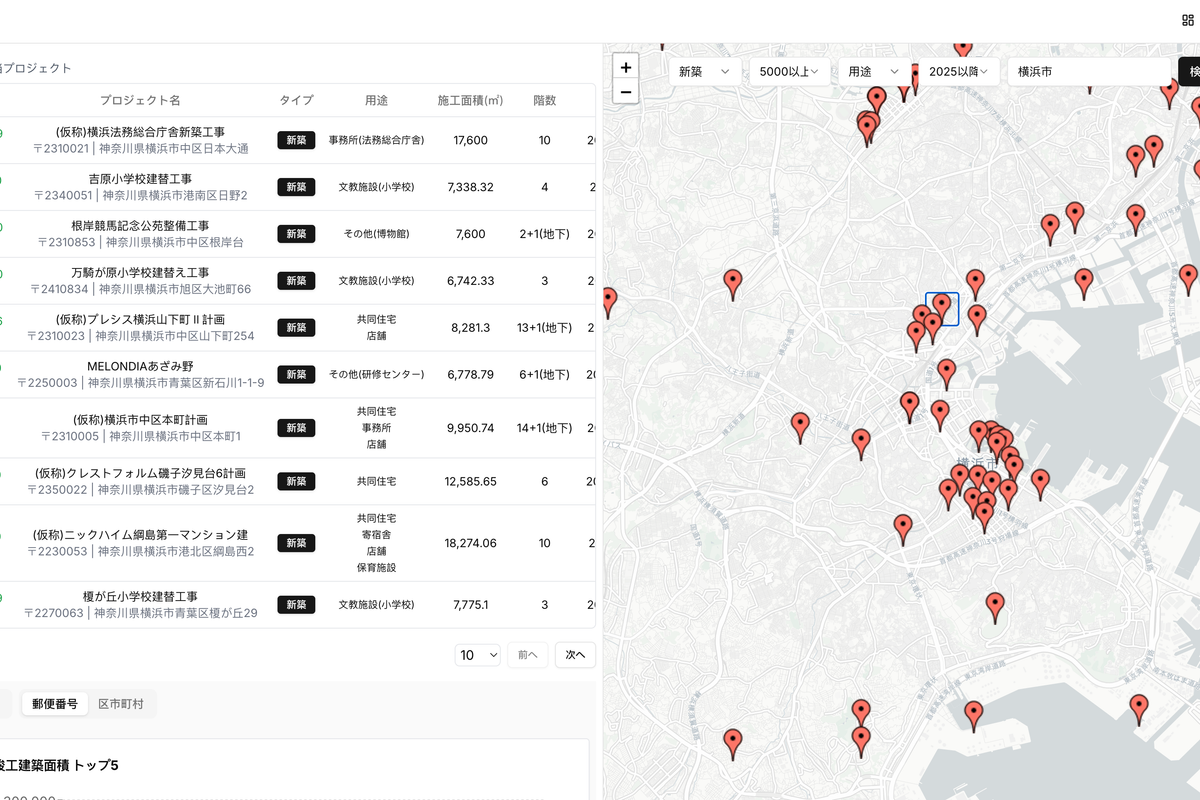

are in areas with large‑scale development plans that help keep vacancy rates low

For example, Urbalytics' development plan map feature lets you view recent development schedules to screen for areas and properties with population growth potential.

2. Use data to identify "overheated areas" and "technically risky properties"

The market still contains many well‑presented listings whose yields are over‑packaged. Investors should:

look beyond "headline yields" and incorporate estimates of "restoration costs" and "repair life‑cycle analysis"

be wary of sellers using technical gimmicks to unsustainably inflate rents

watch for old seismic‑standard buildings or areas with unsustainably high vacancy where refinancing after 2025 may be impossible

For example, Urbalytics' rent‑market comparison tool can test whether current rents are inflated or depressed, helping users avoid attractive‑looking but high‑risk investment traps.

3. Rebuild holding models and exit strategies with interest‑rate scenarios

With the BOJ in a long‑term tightening cycle, investors should stop assuming "permanently low financing costs" and instead incorporate long‑term rate scenarios of 1.0%–1.5% into asset models:

use cash‑flow simulation tools (e.g., Urbalytics) to forecast NOI/ROE under different financing conditions;

design 3–5 year exit strategies prioritizing liquid assets or properties with redevelopment or higher‑value conversion potential;

implement "pre‑refinancing plans" and "reserve provisioning strategies" for existing high‑leverage properties.

References

https://www.tson.co.jp/media/rei/390/ — What was the "Kabocha no Gensha" incident?

https://www.murc.jp/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/medium_1603.pdf — Medium‑term outlook for the Japanese economy (FY2015–2030)

https://diamond-fudosan.jp/articles/-/1111543 — Forecasts that 10‑year variable mortgage rates will rise to 1.493%–2.892%: simulation of 12 banks (2025 latest projection)

Copyright: This article is original content by the author. Please do not reproduce, copy, or quote without permission. For usage requests, please contact the author or this site.