Words: 2712 | Estimated Reading Time: 14 minutes | Views: 746

Niseko, Hokkaido's renowned ski resort, was once hailed as a miracle of Japan's tourism industry. But the real estate bubble in this "resort paradise" has been rapidly deflating in recent years, raising questions about deeper problems in Japan's property market. For investors, this episode concerns not only the rise and fall of a single resort town but also the risks and opportunities created by institutional gaps.

Hokkaido's Niseko: From Skiing Paradise to a Red‑Hot Bubble

Niseko, located in southwestern Hokkaido, is famous for its world‑class powder snow and long stood as a dream destination for skiers at home and abroad. Historically, development here was relatively restrained and the community atmosphere was simple and peaceful—quiet outside the winter peak. However, since the early 2000s, with affluent visitors from Australia and other parts of Asia arriving in droves, Niseko's land values were rediscovered and foreign capital flooded in. Villa plots near the ski areas rose severalfold in a few years, international investors competed to buy land for development, and high‑end resort projects multiplied. In a short span, a tranquil mountain village transformed into a playground for global capital. Yet the overheated speculative boom also planted hidden risks. Local government data still shows rising land prices around the Niseko ski areas, with the 2024 officially posted land price jumping 9.5% year‑on‑year. Beneath the prosperous surface, however, ominous signs are emerging: idle plots, half‑finished abandoned projects, investors who have fled, and a community vitality that is slowly eroding. This former ski paradise now faces the dilemma of "prosperity turning into decline," and local residents worry that Niseko may be on the eve of a bubble burst.

Looking ahead, the trajectory of the Niseko area is full of uncertainty. On one hand, the outstanding natural assets remain, but if climate change reduces snowfall, the destination's appeal will be significantly undermined. On the other hand, local society and culture are being fragmented by waves of capital. If excessive speculation cannot be reversed and allowed to destroy the community's foundations, Japan's world‑class resort brand may lose its luster. Niseko's rise and fall reflects the broader story of Japanese tourism real estate: when a "world‑class ski resort" meets global speculative capital, paradise can become a bubble playground. For investors, this is both a vivid historical lesson about regional asset value and a rigorous exam for the future that requires careful analysis.

Review of This Year's Bubble Incidents

In recent years, rumors of a "Niseko bubble collapse" have frequently surfaced in the press. What pushed this latent concern into the spotlight were several high‑profile incidents in early 2025. The most emblematic involved a large, luxury resort development by a developer with Chinese ties, which suddenly halted construction when its funding chain broke. The developer acquired the land through a Japanese subsidiary and began work on what was planned to be Niseko's largest resort. But construction stopped after only about 30% completion when the company could no longer pay contractors and went bankrupt. The half‑finished structures, draped in protective sheeting against the mountain backdrop, looked particularly stark in the summer greenery. This scene quickly became a media symbol of the "Niseko bubble's collapse." Local reporting indicates such abandoned projects are not unique; previously, multiple foreign‑funded projects leveled land and then stalled without attracting attention because they were less conspicuous. This widely publicized stoppage made outsiders, for the first time, tangibly aware of the crisis beneath Niseko's prosperity.

At the same time, Kutchan town authorities revealed another facet of the iceberg — a large number of foreign investors defaulting on taxes, leading to land seizures and auctions. The town notice boards are filled with dense lists of foreign names; this is the legal process of "public notice service" for taxpayers who cannot be contacted. Official figures show that in 2020 there were only a few such delinquency notices, but by 2024 the volume had ballooned to dozens of pages. Town officials concede: "Delinquency in fixed asset tax is especially significant; many owners reside overseas, making collection extremely difficult." In some cases, Hong Kong‑registered owners repeatedly failed to pay taxes and had their land seized in August 2023 and again in September 2024. In 2024 a villa plot near the ski area was publicly auctioned with an opening bid of several tens of millions of yen. Insiders say that this parcel, originally bought by a Tokyo company during the 1988 bubble and left idle for 40 years, was won by a company suspected to have Chinese ties, bringing it back into the hands of international speculators. The game of capital seems to have entered a "second round": derelict land left by the first bubble has been reactivated by overseas funds after 40 years. What remains for the local community, however, is not just a short influx of money but unclaimed tax bills and a hollowed‑out population.

Even more worrisome is the regulatory vacuum that emboldens some speculators. In June 2024, a large‑scale unauthorized clearcutting and illegal construction incident was exposed on the southern slopes of Mount Yotei, and the developer involved again had links to overseas funding. The Hokkaido prefectural government was forced to step in and demand a halt — a rare move. But local residents are skeptical, believing "in the end most violations will be regularized retroactively," and they doubt the government's resolve and capacity to contain the abuses. Hokkaido Governor Naomichi Suzuki acknowledged the problem in the prefectural assembly and said he had urged the central government to ensure that overseas investors comply with domestic laws and regulations. Yet in the absence of firm enforcement mechanisms under current rules, the effectiveness of such appeals remains uncertain. A string of abuses and disputes has cast a shadow over Niseko's international resort image. Behind the dazzling capital inflows, issues such as lost tax revenue, abandoned projects, and unlawful development have emerged repeatedly, and a local society is paying the price for excessive profit‑seeking.

The Speculative Bonanza and Institutional Gaps

The Niseko bubble did not arise in isolation but is the product of multiple interacting factors in Japan's real estate and institutional environment. Economically, this round of the bubble exhibited classic speculative frenzy characteristics: rising asset prices attracted unrelated rent‑seeking actors who further pushed up prices, drawing in yet more speculative capital and forming a self‑reinforcing "bubble cycle." Niseko was originally a quiet snowy village beloved by skiers, whose reputation spread on the strength of its exceptional snow quality. But when overseas real estate developers arrived en masse and vacation homes and hotels were built and sold in quantity, speculators betting on "land prices only go up" began trading aggressively. Longstanding local residents and small businesses with genuine ties to the place were gradually marginalized. As commentators note, the harm of a bubble lies in "an influx of people unrelated to the asset's fundamental base, which displaces the parties who had long‑term ties and affection for it." The community's connection and attachment were replaced by the indifference of capital; once land becomes a pure financial asset, a bubble burst becomes only a matter of time.

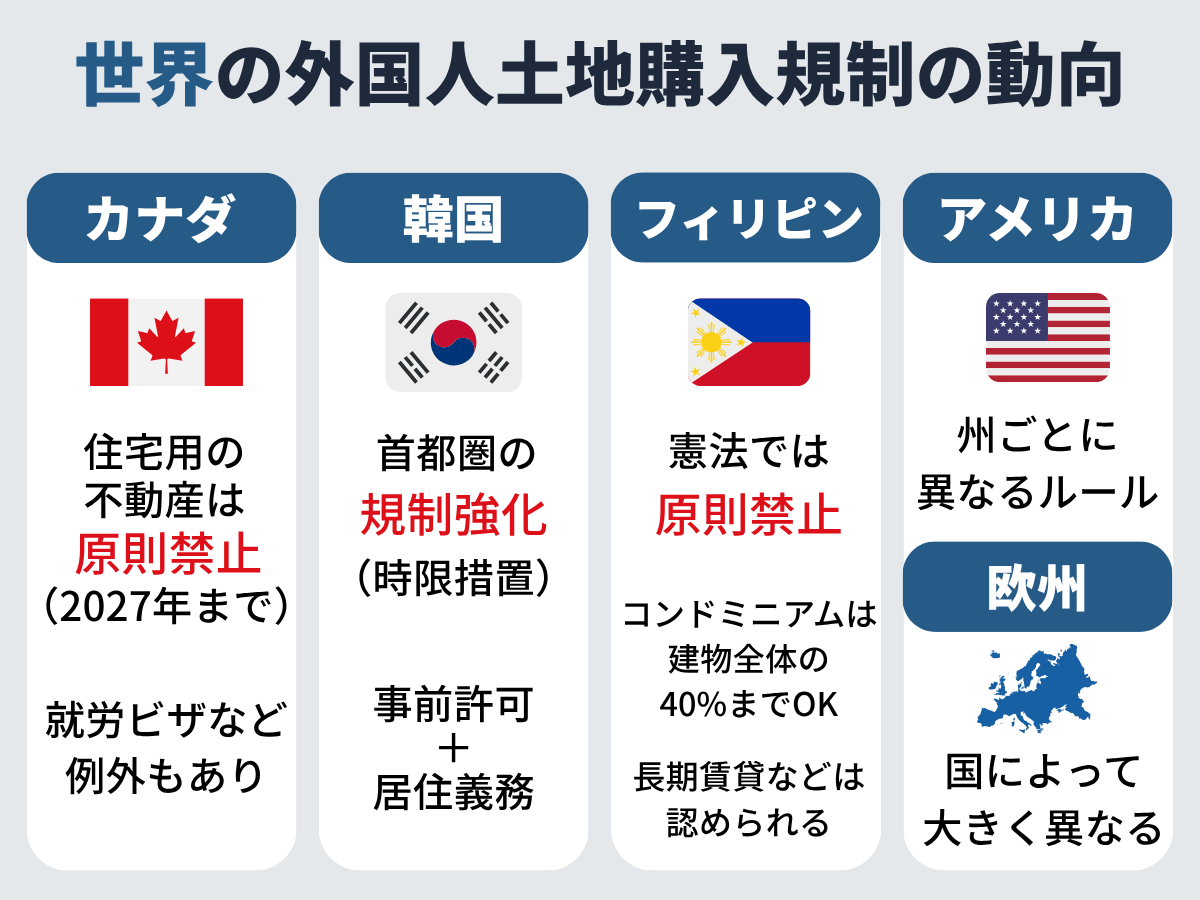

What is particularly alarming are legal and institutional gaps in Japan that left this speculative feast insufficiently constrained and protected. First, there is a lack of effective foreign investment screening and oversight of land transactions. Under Japanese law, private land ownership is constitutionally protected, and individuals and corporations — domestic or foreign — are generally free to purchase land. Local governments have no power to block land sales or refuse foreign capital entry. Some developers obtain land by establishing Japanese subsidiaries, a formality that is legally compliant and outside the reach of traditional preemptive review. It was not until 2022 that Japan enacted the Act on Regulation of Land Use Important for National Security, which introduced prior screening for transactions near sensitive sites such as Self‑Defense Force bases and water sources. But tourist destinations like Niseko are not subject to mandatory oversight, and foreign capital continues to flow in unimpeded. As a result, foreign buyers dominate in Niseko: one survey found that in a newly developed villa area, 7 of 10 plots were owned by foreign individuals or overseas‑registered companies, and five plots were held by offshore entities in the British Virgin Islands. A large number of opaque "paper companies" hold assets, making it difficult to trace actual landowners and complicating later tax collection and infrastructure fee assignment.

Second, weaknesses in tax collection and legal enforcement make it easy for bad actors to exploit gaps. Under the spirit of Japanese law, nationals and foreigners are to be treated equally, so local governments cannot impose special measures on foreign tax delinquents, such as exit bans or compulsory asset seizures abroad. Many foreign owners reside overseas and ignore tax notices sent by mail, creating immense collection difficulties. Kutchan town does have a rule allowing the auction of property to cover unpaid taxes after two years, but the process is lengthy and often comes too late. Publishing delinquent names is currently one of the few measures available to local authorities. This highlights legal lag: facing cross‑border investors who maliciously default on taxes, there is a lack of international cooperation and compulsory mechanisms. Beyond tax, the absence of requirements for developers' post‑project responsibilities is another major loophole. Current regulations do not require developers to post a bond or obtain insurance before starting construction to ensure funds are available for site remediation if a project collapses. The halted, unfinished hotel in Niseko is now in a dilemma: if no new capital takes over, the wreckage could remain for years; the local government lacks authority to forcibly demolish it and cannot afford remediation. Experts recommend introducing a "site restoration bond/insurance" system, requiring developers to deposit funds or secure a policy in advance to cover cleanup if a project is terminated. Such a system is currently absent in Japan and this incident should serve as a regulatory wake‑up call.

Third, infrastructure and public service cost spillovers further expose institutional shortcomings. In Niseko, vacation development driven by foreign capital has overloaded local infrastructure without mechanisms to make developers share the costs. For example, Kutchan's daily water supply demand surged from 3,000 tons to 6,000 tons in a few years, forcing new deep wells to be drilled under Mount Yotei. Plans to raise water fees to fund capacity expansion were shelved for fear of burdening residents. The town initially sought to levy infrastructure allocation fees on new resort developments, but legal limits prevented implementation. As a result, the public fisc and local residents have shouldered these costs while developers have not been required to internalize their commercial externalities. "Regulatory barriers have become a heavy burden on localities," a local official lamented. This situation is not unique to Japan. There have been past controversies in Hokkaido over foreign capital purchasing forest water sources, and without legal prohibitions local governments can do little. The pains experienced in Niseko again demonstrate that Japan's local authorities lack tools to respond to global capital, and the system urgently needs reform.

Risk Insights and Opportunity Strategies

For Japanese real estate investors preparing for turbulence, the Niseko episode provides valuable and nuanced lessons. On one hand, it starkly exposes a list of speculative risks: in an overheated market a bubble burst can leave investors trapped, projects abandoned, or total losses; regions dominated by foreign capital with weak oversight can see sudden policy shifts and public backlash that rapidly deteriorate the investment environment; and soft risks such as infrastructure burden, community conflict, and reputational damage can also dilute investment returns. On the other hand, crisis can create nascent opportunities for investors with foresight and disciplined strategies. During Niseko's bubble deflation, some rational capital quietly repositioned to "pick up the pieces." In July 2025, the stalled project "ラ・プルーム (La Plume)" found a new buyer — an independent Tokyo‑based Japanese investment fund — which purchased the bankrupt developer's asset package at a low price and planned to restart construction in September of the same year. This indicates that for well‑capitalized, patient investors, a retreating bubble can provide opportunities to acquire quality assets at a discount — a classic contrarian investment play. Equally notable is that the Niseko crisis has spurred reform momentum among national and local authorities. For example, in early 2025 the local tourism association and merchants proactively launched a "return to rational pricing" campaign, deliberately lowering some goods and service prices to rebuild reputation and long‑term visitor flows. At one point, some Niseko eateries catered to wealthy visitors with ramen priced as high as ¥3,000 and daily lift tickets at ¥9,500, pricing out ordinary tourists and locals. Today, through efforts by residents and conscientious businesses, "fair pricing" is returning — with accessible menu prices such as curry rice at ¥1,100 and set meals at ¥1,200 reappearing. This shift helps restore Niseko's value‑for‑money reputation and signals a move toward sustainable tourism—positive news for long‑term investors: a healthy, rational market sustains durable returns. Urbalytics recommends focusing on projects and operators that actively coexist with the community and emphasize sustainable operations; these players are likely to stand out during the post‑bubble reconstruction phase.

Investors should also closely monitor policy and regulatory trends and adjust strategies accordingly. The Niseko incidents have accelerated government action. By the end of 2025, news indicated that the cabinet under Sanae Takaichi had placed restrictions on foreign land purchases on the agenda, and related legislative revisions were being actively advanced. It is reasonable to expect greater uncertainty around foreign capital investment in Japan going forward — for example, some areas may introduce purchase permit systems or more stringent disclosure obligations. In response, some international investors are already changing tactics: shifting from quick speculative plays to joint ventures with local partners to improve compliance and community acceptance. Urbalytics' research also shows that investors with local networks and a long‑term operating strategy are better able to withstand policy changes and market shocks than pure financial speculators. Practically, we advise investors to conduct scenario analysis: if the government tightens foreign investment approvals, will current projects be impeded? If tax reform forces investors to shoulder more public costs, how will expected returns change? By stress‑testing scenarios in advance, investors can avoid scrambling to react to regulatory shocks. In terms of geographic selection, diversify — do not concentrate all assets in a single overheated tourism hotspot. When the "next Niseko" becomes the new capital darling, beware repeating the same mistakes. Recent reports indicate Furano and Hakuba are being eyed as new hotspots, with luxury villas and hotels proliferating. Smart investors will learn from Niseko and emphasize fundamentals, community feedback, and clear exit mechanisms when pursuing new opportunities, avoiding being the last player in a game of hot potato.

The story of Niseko is not finished. Whether domestic investors who have taken over stalled projects can successfully revive them, and whether the community can turn painful lessons into an opportunity to build a world‑class yet sustainably inclusive resort, remain matters to watch. If this reform succeeds, other Japanese tourist areas and the broader real estate market will benefit. For investors, a safer and more transparent investment environment and a healthier long‑term market mean higher‑quality investment opportunities. After the noise of a bubble and the pain of its burst, Japanese real estate stands at a crossroads. Rebuilding market ecology based on "trust" and "integrity" will be a collective task for all stakeholders. Only by ensuring that economic development serves a healthy society and that finance returns to supporting real economic value can Japanese real estate investment enter a new golden era. As one observer noted: "The rise and fall of a resort town's bubble may be a reminder not to forget the original purpose of economic activity — everything should aim to create a better society." For investors, the lesson is clear: only by aligning commercial interests with social responsibility can lasting balance be achieved between risk and opportunity.

References

[Source: Toyo Keizai Online, 2025, https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/899331]

[Source: Hokkaido Shimbun, 2025, https://www.hokkaido-np.co.jp/article/1184148]

[Source: TBS News, 2025, https://newsdig.tbs.co.jp/articles/-/2034429]

[Source: Minkabu Finance Magazine, 2025, https://mag.minkabu.jp/politics-economy/37301]

[Source: Huxiu, 2025, https://www.huxiu.com/article/4806031.html]

Copyright: This article is original content by the author. Please do not reproduce, copy, or quote without permission. For usage requests, please contact the author or this site.