Words: 1432 | Estimated Reading Time: 8 minutes | Views: 3306

Both completed in Tokyo from the late 20th to the early 21st century as large-scale redevelopment projects, Roppongi Hills (Roppongi Hills) and Shiodome Siosite (Shiodome Siosite) present markedly different levels of urban vitality and commercial ecosystems. For long-term real estate investors, the differences go beyond tenant brands or building façades; they reflect three decisive factors: “land-assembly capability”, “continuity of urban positioning”, and “user composition”.

Comparing Roppongi Hills and Shiodome Siosite clarifies the key variables for successful redevelopment: aside from location and scale, a project’s ability to identify the city’s cultural touchpoints and everyday consumer entry points directly determines long-term rental income and capital appreciation.

Roppongi: Regional History and Development

During the Edo period, the origin of the name Roppongi is said to derive from either “six trees” or the occurrence of the character “ki” (tree) in the names of six feudal lords. After the Meiji Restoration and as Tokyo expanded, Roppongi gradually transformed from a district of daimyo residences into a residential area. In the Edo period, estates belonging to families such as the Chōfu Mōri and Uesugi clans were concentrated here. From the late Edo period onwards, multiple foreign embassies were established nearby, and the district gradually acquired a strongly international character. Today, traces of the daimyo estates remain within Roppongi Hills—most notably the Mōri Garden.

After World War II, Roppongi’s role shifted further. As a stationing area during the U.S. occupation, it became associated with a foreign residential presence and vibrant nightlife. From the 1970s, leveraging its internationalism and numerous entertainment venues, Roppongi became one of Tokyo’s most famous nightlife districts. By the 1990s, however, Roppongi faced aging urban infrastructure, dense wooden construction, weak disaster resilience, narrow streets, and high fire and earthquake risk. Many wooden structures had low seismic resistance; narrow roads prevented large fire engines from accessing some areas, increasing fire risk. These latent hazards prompted calls to “consolidate larger land parcels” to secure a more desirable urban environment. The renewal needs of TV Asahi triggered a redevelopment initiative in partnership with Mori Building; in 1986 the Tokyo government designated Roppongi 6-chome as an inducement area for redevelopment, initiating land rights consolidation and urban renewal. Mori Building’s leadership in driving the project can be said to have laid the foundation for Roppongi Hills’ future.

Shiodome Development in the Same Period

Shiodome, located in Minato Ward adjacent to Shimbashi, Ginza and Hamamatsuchō, has roots in the Edo-period shogunate land reclamation and concentration of samurai residences. After the Meiji Restoration, it became a pioneer site for Japan’s railways: in 1872 Japan’s first railway, the Shimbashi–Yokohama line, opened, and the old Shimbashi terminal was located here. With the opening of Tokyo Station in 1914, the old Shimbashi terminal was converted to Shiodome Station and later became a freight-only facility.

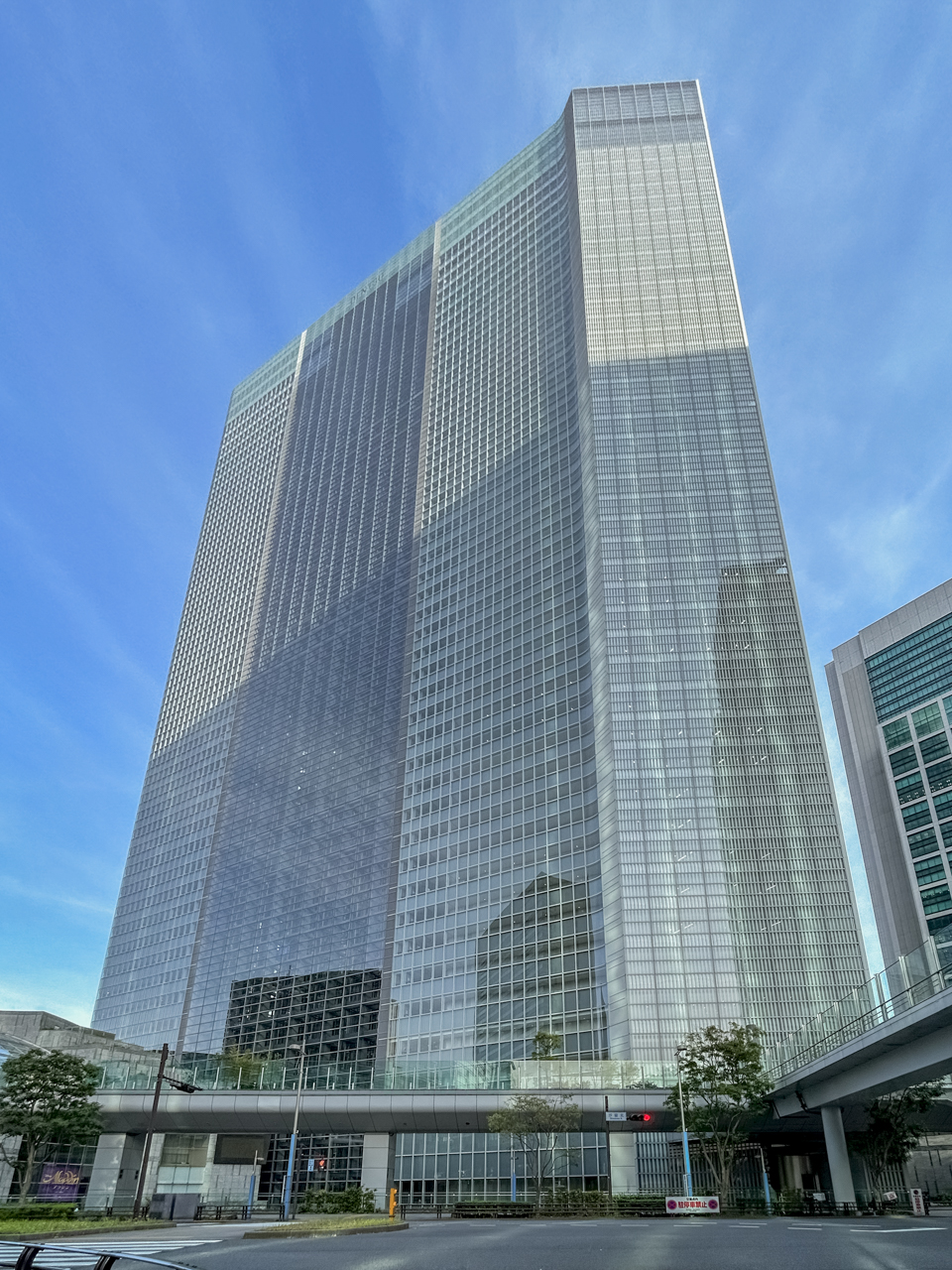

Over time, in 1986 the old JNR Shiodome freight yard was decommissioned, creating more than 22 hectares of railway land in central Tokyo—an exceptionally rare large urban vacancy. The Tokyo metropolitan government, Minato Ward and private consortia subsequently formulated the Shiodome Area Comprehensive Redevelopment Plan. Based on that plan, redevelopment in the Shiodome area formally began around 1995. The site covers approximately 31 hectares across 11 blocks, with the objective of integrating office, retail, cultural and residential functions. In 2002 the development area was named “Shiodome Siosite” (SHIOSITE) and opened to the public.

Compared with Roppongi’s concentrated partnership, Shiodome’s redevelopment originated from the abandoned JNR freight yard and involved a large-scale reconfiguration from scratch. Local government and several major developers (such as Dentsu, Mitsui Fudosan, and Nippon TV) each obtained blocks to develop, resulting in a district composed of several independently developed parcels rather than a single unified plan.

After completion, the area quickly became a high-rise concentration in central Tokyo. Representative projects include Caretta Shiodome, Shiodome City Center, and Shiodome Media Tower. Corporate headquarters, hotels, shopping centers and convention facilities moved in. Major companies such as ANA, Fujitsu and Nippon TV relocated to the area. However, entering the second decade of the 21st century, questions began to surface about Shiodome’s “vitality.” Although skyscrapers rose, the district did not generate the anticipated level of pedestrian activity outside office hours (particularly evenings and weekends). Media outlets observed that Shiodome is often dubbed “withered Shiodome” in the evenings and on weekends. One reason is that commercial uses are skewed toward offices, the resident population is relatively low, and nighttime activity is weak.

Integrated vs. Fragmented Development: Current Conditions

Roppongi Hills’ development was led by Mori Building, achieving a high degree of consistency in land-assembly, design control and mixed-use planning. The project includes premium offices, luxury residences, apartments and retail, and places cultural facilities (such as the Mori Art Museum) at its core—willing to sacrifice short-term maximum rents in order to build long-term brand recognition and a steady base of visitors. This “cultural city-center” positioning is continually reinforced through exhibitions, festivals and district activities, strengthening the bond between landowner and users.

Shiodome Siosite’s development, by contrast, progressed under multiple lead developers. Despite a larger land area, fragmented development resulted in limited ground-floor retail frontage, retail offerings skewed toward office lunch/takeout needs (a high proportion of F&B), and public spaces that primarily serve the weekday office population. Although cultural facilities such as the Ad Museum Tokyo and the Four Seasons Theatre exist, they are often located on lower floors or within limited footprints and have not become sustained engines of the area’s cultural ecosystem.

Trends in Population, Land Prices and Leasing Demand

Analysis of land prices (MLIT public land prices and Tokyo benchmark land prices) and Minato Ward statistics shows: due to strong demand for high-end offices and residences, Roppongi’s commercial land prices in core locations have continued to form premium corridors after opening; Shiodome’s office land prices have remained relatively firm, but commercial land price momentum—especially for retail and leisure—has been more limited compared with Roppongi.

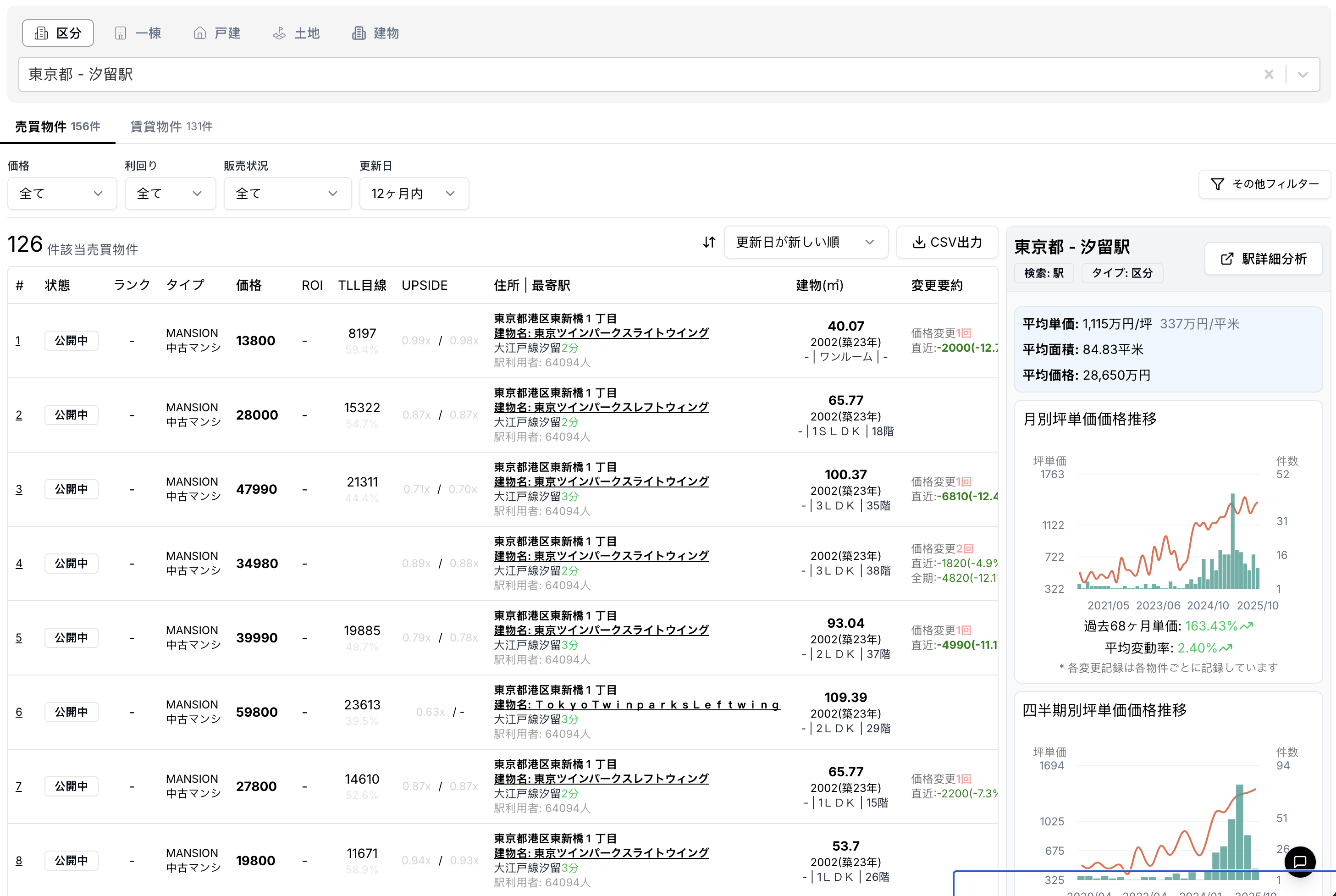

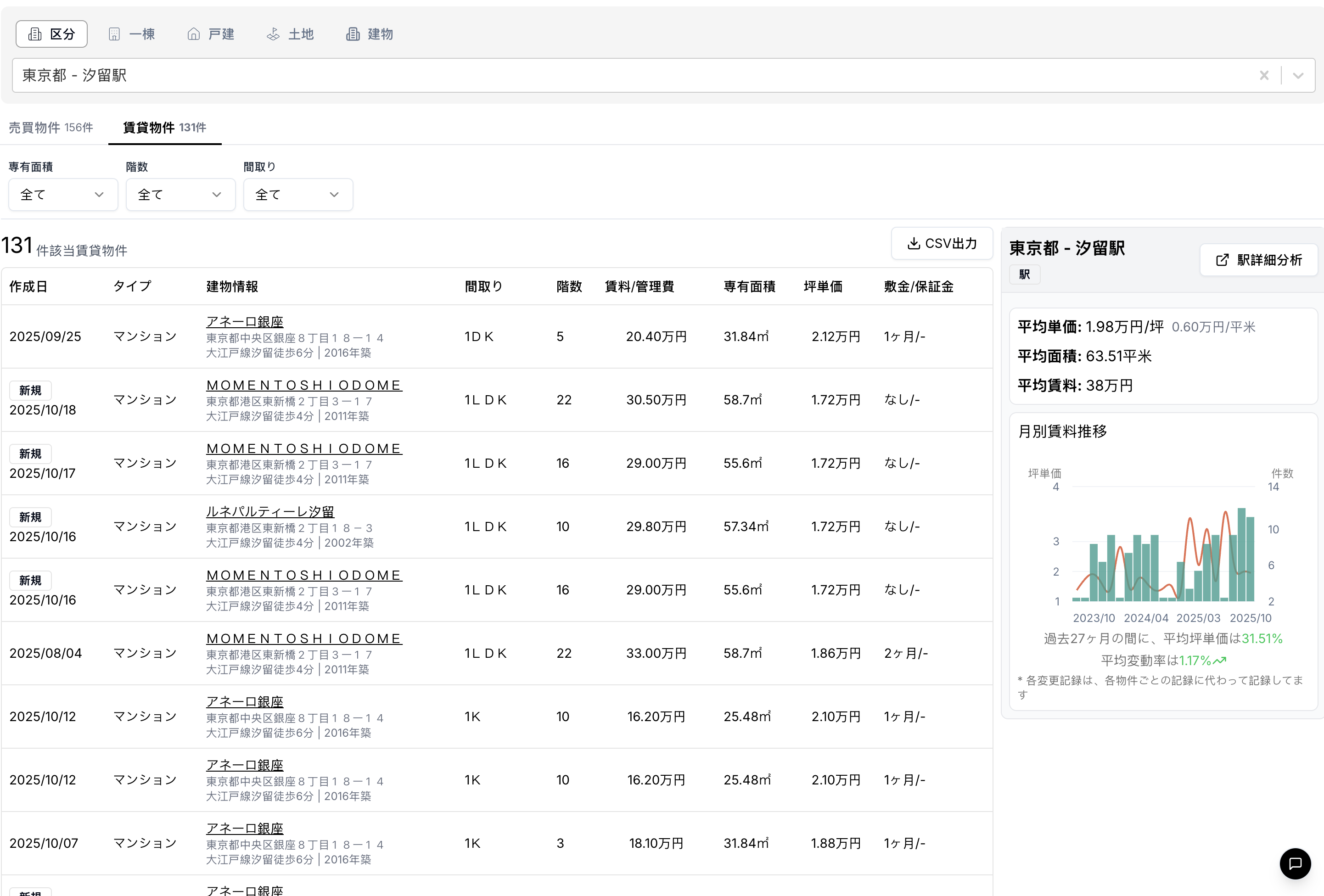

On the sales side, Urbalytics’ condominium data indicates that Shiodome’s average unit price nominally rose about 163% in the past five years, with a nominal monthly increase of roughly 2.4%. Over the same period, Roppongi’s condominium prices rose approximately 240%, about 1.5 times Shiodome’s growth. (Note: the above are outputs from Urbalytics’ simulation model provided for investment decision reference.)

On the rental side, Shiodome’s current average is ¥19,800 per tsubo, with typical monthly rents around ¥380,000. By contrast, Roppongi’s apartment rents reach about ¥24,800 per tsubo—approximately 1.2–1.3 times those in Shiodome.

Investment Opportunities and Risks

Roppongi Hills exhibits two key characteristics: “highly sticky demand” and a “cultural premium.” For investors seeking stable rental income and capital preservation, premium offices and branded retail in this district remain top choices. In addition, luxury residences and serviced apartments benefit from Roppongi’s international image and the draw of its cultural activities for long-term leasing markets.

Shiodome’s opportunity lies in the long-term demand for an institutional office cluster. If an investor prioritizes stable tenants (such as large corporate headquarters and media companies) and a relatively high tenant concentration, Shiodome’s office product can deliver comparatively predictable cash flows. However, its retail and experiential assets face structural challenges: insufficient weekend and discretionary consumer traffic suppresses revenue upside for dining and retail.

On the risk side, Roppongi is not without concerns. High rents, taxes and maintenance costs mean a high investment threshold; dependence on short-term tourism and event-driven footfall raises sensitivity to macroeconomic and tourism-policy fluctuations. Shiodome’s principal risk is a “single-use bias”: if the office-demand structure changes (for example, if remote work becomes widespread or companies relocate), Shiodome’s foot traffic and retail revenue elasticity would be weak and the cost of asset repositioning would be high.

Conclusion: "Place + Experience-driven Operations" Determine Long-term Value

The comparison between Roppongi Hills and Shiodome Siosite shows that equal or even superior land scale does not automatically translate into long-term commercial success. What truly drives long-term asset value is continuous investment in place positioning, unified and decisive execution of planning, and the operational capability to bring people (not just office tenants) into the district. For investors evaluating large-scale redevelopment projects, due diligence should look beyond land prices and rent figures to include governance structure, degree of land-rights integration, and the supply of cultural programming and activities.

In Tokyo’s premium core, Roppongi Hills provides a model of leveraging culture to create an urban icon; Shiodome serves as a reminder that scale alone cannot substitute for consistent place expression and a long-term operational strategy. Future opportunities will favor assets that can both deliver high-quality space and continuously generate multi-period footfall and experiential value.

Copyright: This article is original content by the author. Please do not reproduce, copy, or quote without permission. For usage requests, please contact the author or this site.