Words: 2274 | Estimated Reading Time: 12 minutes | Views: 514

The Japanese real estate market recently revealed an investment scam: a veteran investor, having trusted a "sute-kanban" (an illegally posted roadside property advertisement on a utility pole), lost a JPY 20 million deposit to unscrupulous operators. This incident exposes institutional gaps and investment risks in property transactions that all domestic and international investors should heed.

Regional background: a sober reassessment of the solar boom in a Kagawa town

The story unfolds in Mannō Town, a small municipality in Kagawa Prefecture on Shikoku Island. This rural area experienced a wave of solar investment fervor in the early 2010s. After Japan introduced the feed-in tariff (FIT) for renewables in 2012, photovoltaic projects proliferated nationwide. Sunlit, low-cost rural land suddenly became highly sought after, and areas like Mannō Town saw what could be described as a "solar bubble," drawing many outside investors searching for suitable plots. As subsidies tapered, the craze cooled and many rural development projects collapsed. On one hand, local governments began rethinking how to balance renewable energy development with agricultural land protection; on the other, the boom left lingering risks: information asymmetries created opportunities for bad actors to take advantage of outside investors. Against this backdrop, Mannō Town embodies both the past rush for profits and today’s cautionary lesson for rational, prudent investors. Looking ahead, as Japan tightens land transaction oversight and encourages digital transparency, rural investments should become more transparent and regulated. But until regulatory improvements are fully implemented, such areas may continue to present simultaneous temptations and risks—reminding investors to recognize rural real estate opportunities while maintaining vigilance and restraint.

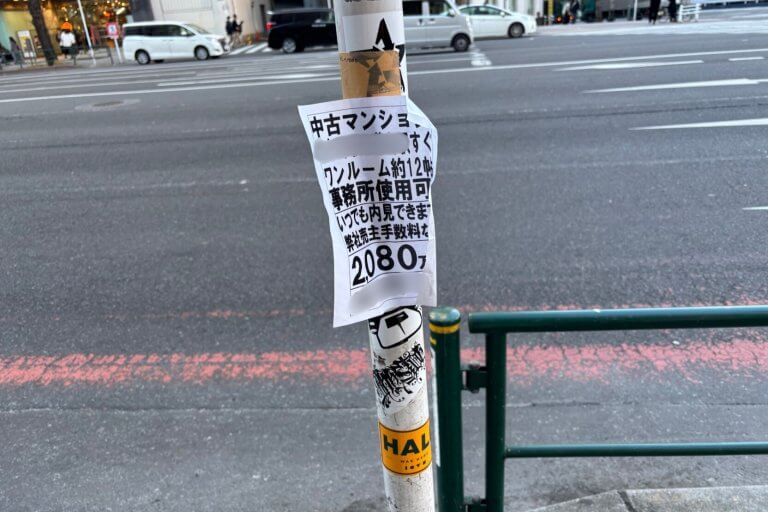

Around 2012, an experienced investor nicknamed "Masa" (alias) went to Kagawa looking for land for solar development. He had about 20 years of real estate investing experience but was attracted during a chance drive by to a simple property advertisement pasted on a utility pole. The ad claimed a 22-hectare "sunny gem" was for sale at JPY 3,000 per tsubo—putting the total below JPY 2 billion, a fraction of comparable Tokyo land prices. The ad did not display a company name, only a landline and mobile number. Although Masa felt the roadside flyer was somewhat informal, he still called. The person who answered claimed to be the president of a one-man company and presented himself as an intermediary; he professed solar-land transaction experience and knowledge of farmland conversion approvals, persuading Masa of his professionalism. At the time, solar land was scarce, and fearing he would miss the opportunity, Masa hastily agreed to purchase and, together with a partner, each paid a JPY 20 million deposit. After payment, the seller repeatedly delayed the formal transfer with excuses and ultimately disappeared. Only then did Masa realize he had been defrauded, but it was too late: the operator had absconded with the funds. Later reports indicated the fraudster was arrested in connection with other deposit scams, but the money had already been squandered and Masa’s loss could not be recovered.

In a similar vein, other investors—though not losing money—have suffered serious hassle after responding to "sute-kanban" ads. A Tokyo investor, Mr. Kanda (alias), called a number on a street advertisement for a real estate company, only to learn the listing was not the apartment he sought but an entire detached house in the suburbs being sold as a whole. Sales staff nonetheless aggressively pushed properties that did not meet his needs. Mr. Kanda was subsequently bombarded with persistent sales calls and, in one instance, a salesperson unexpectedly showed up at his office demanding a meeting. From unrealistic property recommendations to relentless recruitment of financial advisors in a "chain-bomb" of solicitations, the harassment exhausted him and led him to abandon the transaction. Although no money was lost, the episode wasted significant time and energy, underscoring that pursuing properties via illegal roadside ads often fails to yield suitable assets and frequently invites protracted trouble.

Institutional loopholes and gray-market tactics

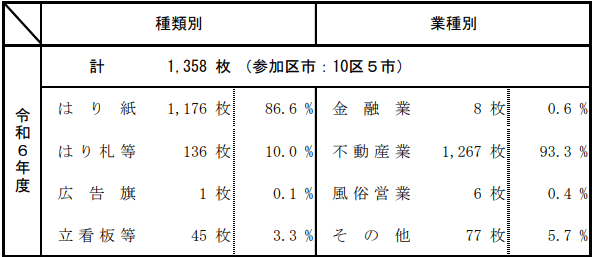

The above incidents reveal several systemic weaknesses and industry malpractices in Japanese real estate transactions. First, these "sute-kanban" advertisements are inherently illegal. Many municipalities prohibit posting advertisements on outdoor public fixtures (utility poles, signs, road cones, etc.). For example, Tokyo’s outdoor advertising regulations aim to preserve cityscape and traffic safety; illegal postings can incur fines up to JPY 300,000. In practice, enforcement is difficult: real estate firms often place such ads surreptitiously at night and remove them quickly after attracting attention on weekends to avoid being caught in the act. When apprehended, they often attribute it to the actions of an individual, not the company. Historically, fines were as low as JPY 5,000—trivial compared with the commission income often worth millions—so bad actors treat penalties as a mere "cost of doing business."

The persistence of illegal ads reflects a mismatch between low enforcement costs and weak regulatory action. In a concentrated cleanup in Tokyo in autumn 2021, authorities removed 1,832 illegal ads within two months, with over 87% being simple paper postings and 82% related to real estate. Although the government annually mobilizes police and volunteers to remove illegal ads and has stepped up efforts in recent years, the sheer volume of these "weed-like" postings remains overwhelming. Many real estate practitioners knowingly take the risk, driven by profit-seeking norms in the industry, which signals the hidden transactional traps behind such practices.

Deeper vulnerabilities lie in the trust chain of real estate transactions, which fraudsters exploit. Japan’s property transactions rely heavily on intermediaries and paper documentation, creating openings for scammers. For example, the scam encountered by Masa was essentially a deposit fraud orchestrated by a "fake broker": fraudsters register a one-person real estate company, lure investors with too-good-to-be-true offers for premium, low-priced plots, then use forged identities and false promises to steal sizable deposits before disappearing. Such schemes are not isolated—one notorious 2017 case involved the developer Sekisui House, which was targeted by an elaborate "land swindle". Sekisui House paid a total of JPY 5.5 billion before discovering the transfer applications were fraudulent and the sellers were impostors. This shocking case highlighted multiple flaws: identity verification of titleholders was superficial, transactions relied excessively on easily forged paper documents, and internal controls were weakened by profit incentives. In response, the government and industry bodies implemented countermeasures—such as tightening real estate registration procedures at the Ministry of Justice and introducing a "prevention registration" system allowing landowners to file alerts with registration authorities to receive warnings if unauthorized changes are attempted. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) also strengthened oversight of real estate brokers, reiterating provisions of the Real Estate Transaction Business Act and the Fair Competition Rules for Real Estate Display prohibiting false advertising; "otori" (bait) ads that misrepresent listings face stricter penalties. Brokers who post non-existent or already-sold listings can face business suspensions, license revocation, and even criminal penalties—up to six months' imprisonment or fines of up to JPY 1,000,000.

Even so, infractions persist: in 2022 alone, authorities across Japan issued administrative sanctions for 421 instances of false or bait advertising in real estate. Evidently, the lure of huge profits still tempts a minority of practitioners to post misleading information to attract clients and then resell other properties for gain.

For investors, this confluence of industry disorder and legal gaps means: never take surface information at face value when investing in Japanese real estate—especially if a transaction deviates from normal procedures, exercise heightened skepticism and verify independently.

Investor perspective: risk alerts and mitigation strategies

From an investor’s standpoint, the lessons are clear. First, high-return allure often accompanies high risk; the more a deal looks like a "too-good-to-miss" bargain, the more scrutiny it requires. Masa ruefully notes that he always followed the rule "inspect the seller first," valuing counterparty credibility over the asset itself. Yet influenced by peers at the time, he relaxed his vetting of the information source and blindly trusted an unverified roadside flyer, leading to the trap. This warns all investors: regardless of market heat, adhere to basic due diligence. Any transaction that breaks conventional procedures may conceal unconventional risks. Contacting sellers via roadside ads is already outside regular channels; if the counterparty pressures for quick payment or refuses to disclose company details, these are red flags. Investors should halt and avoid gambling on luck. In Japan, transactions should generally proceed through licensed real estate brokers; verify the broker’s license number (宅建業免許) and trade association membership. If unavoidable to deal directly with a seller, hire a judicial scrivener (a legally recognized professional) to verify land registry records and title before paying any deposit. For deposit handling, insist on signing a formal contract and placing funds in a third-party escrow account until title transfers—this parallels escrow practices elsewhere. While not mandatory in Japan’s secondhand market, investors can proactively request escrow to safeguard funds.

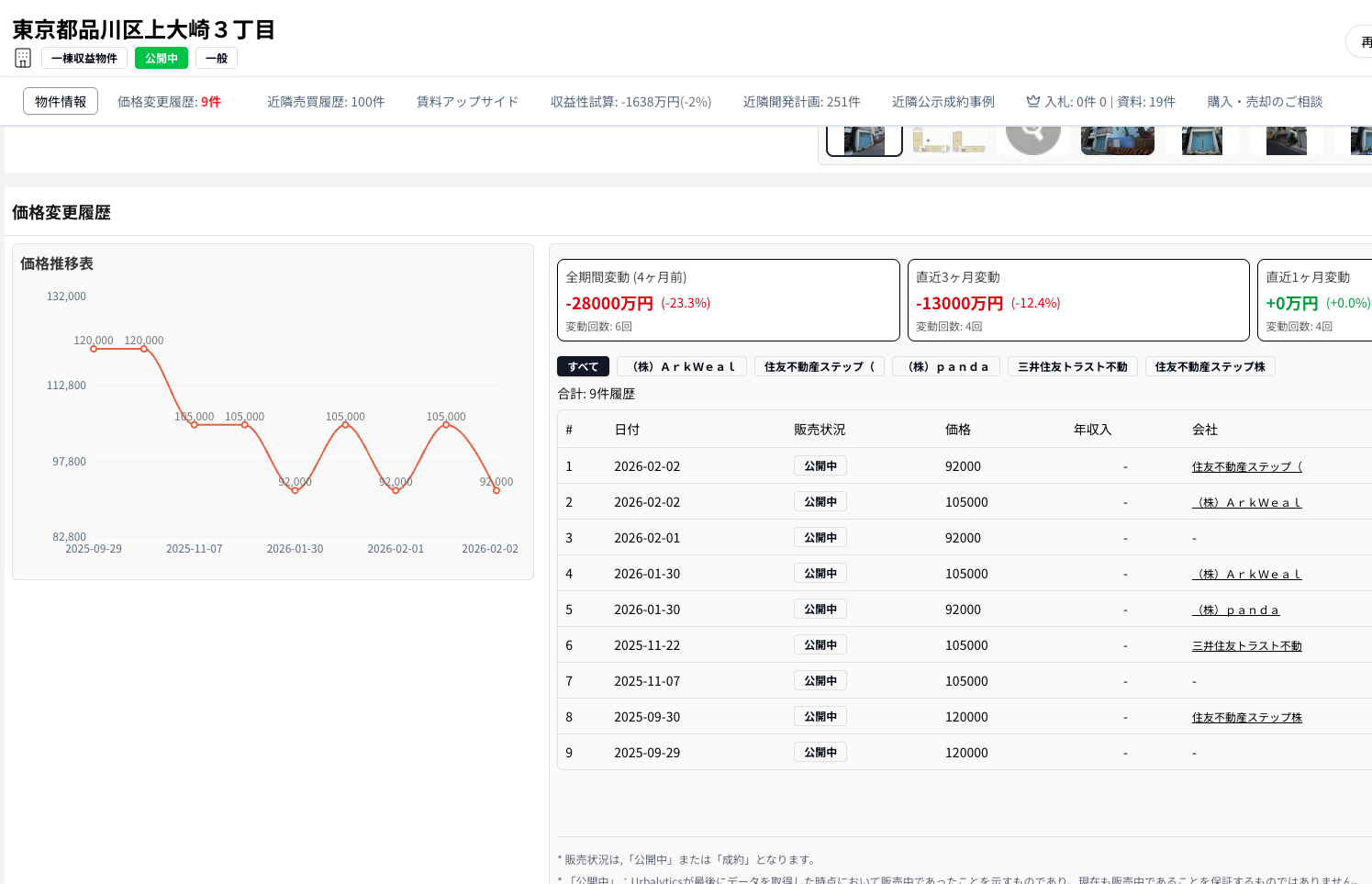

Second, do not be swayed by the artificial urgency created by illegal ads. Scammers exploit investors’ fear of missing out with tactics like "limited-time offers," "insider information," or "exclusive listings" to force hasty decisions. Masa was swept up by the atmosphere of "solar land is hot," relaxing his guard. Investors must remain calm in any market condition. If a deal lacks basic transparency—no company name on the ad, pricing far below market, ambiguous salesperson behavior—resist acting impulsively and independently verify the facts. Modern tech offers powerful tools: platforms like Urbalytics allow investors to quickly check a target parcel’s transaction history, comparable market prices, and planning restrictions. Had Masa compared data, he would have found that the advertised JPY 3,000 per tsubo was far below typical local prices and therefore implausible. For listings without explicit addresses, investors can use GIS maps, street-view imagery, and other public resources to locate and verify the asset. On-site visits are sometimes necessary—confirm whether the parcel is truly vacant, whether there are title disputes, or whether geographic defects (mountainous terrain, marshland, etc.) reduce value. In short, ask a few more investigative "why" questions: why was this not listed through normal channels? why is the seller urgently divesting? does the information withstand scrutiny? The more skepticism, the greater the protection.

Finally, Mr. Kanda’s experience offers another lesson: respect your time and reputation—do not let unscrupulous brokers control you. If it’s obvious that the property does not match your criteria or the broker uses disrespectful coercion, withdraw promptly to cut losses. Real estate investment requires rational planning and professional judgment; legitimate opportunities come through regulated marketplaces and trusted networks, not from ubiquitous roadside flyers. Rather than wasting time on low-quality intermediaries, focus on analyzing market data and inspecting quality assets. Real investment opportunities typically do not appear on utility poles; valuable listings are found on professional platforms, within trusted broker networks, or uncovered by data-mining tools. For example, using Urbalytics’ big-data filters, investors can screen for undervalued assets by rental yield and regional growth indicators and then work with licensed firms to negotiate transactions. Such a compliant, data-driven approach is both efficient and risk-controlled, far superior to gambling on chance via street ads.

Conclusion: regulatory reflection and prospects for investment safety

This scam triggered by a "sute-kanban" reflects dual vulnerabilities in Japan’s real estate market: weaknesses in law enforcement and market discipline. On one hand, the persistence of illegal roadside ads nationwide indicates room for regulatory improvement. Fortunately, the government has begun stronger crackdowns: in addition to regular removals of illegal ads, laws have been strengthened. For example, the 2024 revision of the Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations enhanced penalties for false advertising to increase deterrence across industries including real estate. It is foreseeable that the operating space for illegal roadside ads will shrink and that penalties for violators will grow steeper. On the other hand, the incident draws attention to the need for deeper reforms in transaction systems. From the Sekisui House scandal to individual investors’ lost deposits, each case has pressured authorities to close procedural gaps. Japan may further implement stricter identity verification for title changes, adopt electronic notarization for real estate transfers, and introduce blockchain-based recordkeeping to prevent impersonation of owners and similar scams. Industry associations should also strengthen self-regulation, encourage members to comply with rules, ban false advertising, and impose severe sanctions or market exclusion on violators. Implementing these measures will help create a more transparent and secure investment environment.

For investors seeking to establish assets in Japan, the most important takeaway from this incident is education and prevention. Real estate investing is not a speculative game of pure profit-seeking; it should be a rational process conducted within legal and regulatory frameworks. Every investor should learn from this: exercise prudence in matters affecting your wealth, comply with local laws, and respect market common sense. Use official channels and professional tools to obtain information—and always verify before committing funds. When faced with an opportunity that seems like a "free lunch," add a measure of sober reflection and resist impulsive action; that alone may prevent falling into a scam. As the old adage goes, "invest wisely, be careful from start to finish." Only by fortifying common sense and the rule of law can investors navigate volatile overseas real estate markets steadily, grow wealth, and protect their gains.

References:

Source: Kagawa Prefectural Government, 2023, https://www.pref.kagawa.lg.jp/junkan/ce/solar/index.html】

Source: SIGN News, 2021, https://www.sogohodo.co.jp/administration/9993/】

Source: Dramago (PTS, Taiwan), 2024, https://dramago.ptsplus.tv/articles/17984/】

Source: Diamond Real Estate Research Institute, 2024, https://diamond-fudosan.jp/articles/-/1112410】

Source: Realty Company Support, 2024, https://f-mikata.jp/rosette-423/】

#RealEstate #JapanRealEstate #InvestmentRisk #IllegalAdvertising #BaitAds #DepositFraud #LegalLoopholes #MarketRegulation #SolarInvestment #RealEstateStrategy #InvestmentLessons #RiskPrevention #Urbalytics #DataAnalytics #CrossBorderInvestment

Copyright: This article is original content by the author. Please do not reproduce, copy, or quote without permission. For usage requests, please contact the author or this site.