Words: 2187 | Estimated Reading Time: 11 minutes | Views: 11097

Recently, a shocking real estate fraud unfolded in one of Osaka’s busiest commercial districts: a criminal group impersonated property owners and, under the guise of legitimate transactions, fraudulently obtained more than ¥1.45 billion. These so-called “land swindlers” repeatedly succeed by exploiting weaknesses in Japan’s property transaction system, sounding an urgent alarm for investors. For professional investors involved in high-value deals, this is more than a headline — it is a powerful lesson in risk management: how can one protect capital when navigating complex regulations and tempting transactions?

Case Summary

In September this year, the Osaka District Court heard a case involving a land swindler fraud. Defendant Hiroshi Fukuda (53) is accused of colluding with others to impersonate representatives of property-owning companies and, between February and March last year, “sell” three commercial buildings in Osaka’s central, high-traffic area (commonly known as “Minami”) to two real estate firms, thereby obtaining approximately ¥1.45 billion. Investigations show the fraud ring operated with clear division of labor: two female members posed as representatives of the property-owning company and a relative, forging identity documents in advance and registering fake seals (inkan) at the ward office; a younger male then posed as the owner’s grandchild, claiming to have inherited the company’s ownership and presenting falsified ID. The forged documents were convincing enough that even the judicial scrivener (the Japanese specialist responsible for property transfers) on site did not detect the forgery. Contracts were swiftly signed — one building changed hands for about ¥450 million with large amounts of cash delivered in a suitcase on the spot; days later, two other buildings were “sold” for about ¥1 billion in total, with the buyer making substantial cash payments after signing. The scam only unraveled weeks after the real owner engaged lawyers. Clearly, the swindlers staged transactions to appear legitimate, collected funds quickly and vanished, leaving the purchasing companies with massive losses.

Notably, this is not an isolated incident. The term “land swindler” derives from the Japanese name for fraudsters who impersonate landowners. As far back as 2017, Japan’s well-known homebuilder Sekisui House fell victim to a similar scam: trusting forged seller identities, it lost around ¥5.5 billion, sparking public outcry. Investigations then revealed that the company had paid large deposits and sums during the land transactions and only discovered the problem when its registration application was rejected by the Legal Affairs Bureau — by then the funds had already been transferred away. Although arrests followed, the ¥5.5 billion loss has not been fully recovered. The Osaka incident mirrors the Sekisui House case, demonstrating that even top-tier companies and seasoned professionals can be caught off guard. For all real estate investors, this case is a warning: what systemic gaps in Japan’s property transaction process are being exploited, and what lessons should investors draw?

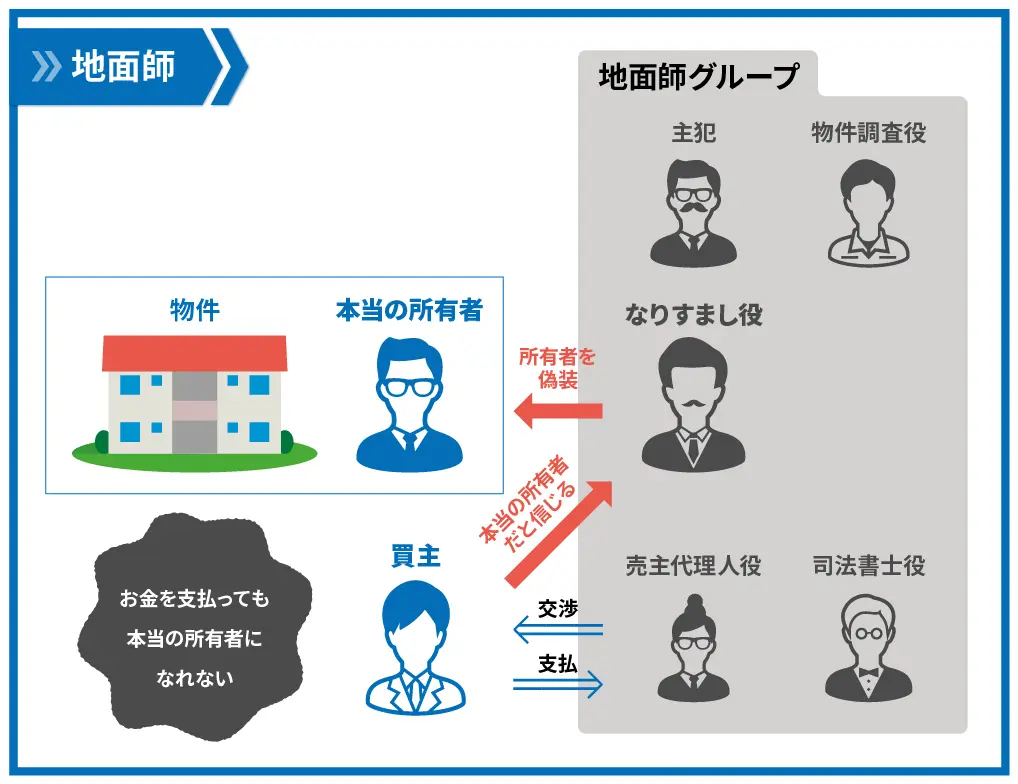

Systemic Gaps and Common Tactics of “Land Swindlers”

Reliance on Paper Documents for Identity Verification

To understand how these scams succeed, one must first grasp the characteristics of Japan’s property transaction system and the typical tactics of land swindlers. In Japan, real estate transactions usually depend on paper documents and seal (inkan) verification. When an owner sells property, they are required to present government-issued seal registration certificates and identity documents. However, this mechanism contains inherent vulnerabilities: if criminals can obtain or forge these documents, they can impersonate registered owners and execute transactions. In the Osaka case, the fraud ring exploited procedural gaps to illegally obtain genuine family registry extracts, then used them to forge IDs and seal registration certificates, making themselves appear as recorded legal owners before the transaction. They even infiltrated the ward office in advance and, by submitting fake documents, secured a seal registration that altered official records — thus paving the way for subsequent bogus sales.

Credibility Issues in the Real Estate Registration System

Second, land swindlers exploit the credibility limitations of Japan’s property registration system. In Japan, land registration is not absolutely conclusive — the registry does not guarantee authenticity to third parties. That means even if fraudsters register themselves as owners, the true owner can later claim the registration is invalid; resolving such disputes, however, requires time. Land swindlers exploit this time lag: after fraudulently obtaining “ownership,” they rush to complete sales, collect funds, and disappear. In the Sekisui House case, the criminals submitted false ownership transfer applications and took large sums from buyers; the true owner completed inheritance registration shortly after, exposing the fraud — but the funds could not be recovered. This highlights deficiencies in slow registration procedures and weak anti-forgery measures. When days to a week may elapse between contract signing/payment and registration taking effect, fraudsters find an opening. Even worse, registration authorities lack immediate means to verify document authenticity: if a forged passport or driver’s license is highly convincing, even experienced professionals or police may not detect it on the spot.

As industry commentators have noted, “under the current property registration system, it is nearly impossible to immediately detect cleverly forged documents” — a conclusion repeatedly validated by land swindler cases.

Weaknesses in the Funds Transfer Process

Another vulnerability lies in imperfect funds transfer procedures. In many countries, high-value property transactions are typically executed through third-party escrow accounts, with buyer funds released to the seller only after ownership transfer is confirmed. In Japan, however, traditional practice often involves transferring funds directly to the seller or their agent, and in cases like the Osaka incident, even settling in cash on site. This approach lacks a financial buffering mechanism; if the seller’s identity is fraudulent, funds immediately end up in the swindlers’ hands and are extremely difficult to recover. Comparative analysis points out that Japan’s lack of a mandatory escrow mechanism created opportunities for land swindlers — by contrast, regions such as Taiwan require buyer funds to be deposited into escrow until the transaction is verified, greatly reducing fraud risk. This flaw in Japan’s transaction practices has prompted industry-wide reflection in recent years.

In summary, the success of land swindler fraud depends on multiple systemic weaknesses: identity verification relies on forgeable paper documents; registration and funds transfer processes create time gaps; regulatory oversight and escrow mechanisms are insufficient; and the lure of large profits sometimes leads parties to relax caution and prioritize speed. Fraud rings are typically well-versed in legal and transactional procedures and prepare in advance: they favor assets with lax oversight (idle land, properties registered to solitary elderly owners, or corporate assets), create a sense of urgency (pressuring buyers to pay quickly or claiming competing bidders), and play multiple roles (posing as family members, agents, lawyers, or notaries) to manufacture credibility. If investors or intermediaries lapse at these touchpoints, they can easily fall into traps.

Investor Perspective: Lessons and Practical Safeguards

For real estate investors, the lessons are stark: no institution or veteran professional is immune to a moment’s lapse in vigilance. If a publicly listed company like Sekisui House can be defrauded, individual investors must be even more cautious and not over-rely on customary practices or surface-level materials provided by the counterparty. The following risk pointers are distilled from recent cases:

Verify the owner’s identity meticulously: Do not fully trust identity and ownership documents provided by the other party. Before signing, insist on meeting the owner in person and carefully checking original identification documents; where necessary, request additional corroboration (for example, original receipts or historical documents related to the property). If the seller is a company, verify the signer’s authority via company registration records and confirm the transaction directly with company management. As professionals advise, “Confirm the true identity of the house or land owner before signing” — even if it lengthens the process, this step is indispensable.

Use multiple channels to cross-check information: Leverage public records and third-party advisers for cross-verification. For example, compare the name recorded on the property registry with the photo ID and trace recent ownership changes to confirm legitimacy. Following the Sekisui House incident, some practitioners recommended neighborhood inquiries to validate the owner’s identity (e.g., asking neighbors or building management about the property owner) — a traditional but effective method to detect anomalies beyond paper records. For cross-border or unfamiliar markets, engage specialized law firms or due-diligence providers to investigate ownership history.

Watch for suspicious transaction behavior: Unusual terms are often red flags. Examples include overly attractive prices, pressure to complete or pay in an unusually short time, preference for cash payments, or reluctance to disclose required information. In the Osaka case, the seller’s insistence on an on-site cash settlement was itself suspicious. Experienced investors know that when the counterparty entices with low prices or rapid closing, be alert to potential fraud. In such situations, compare prices across multiple listings, consult industry peers about market norms, and, if necessary, pause the transaction for deeper investigation.

Enlist professional expertise: High-value real estate investments demand a “spend to secure” mindset. During transactions, ensure independent third parties such as lawyers and judicial scriveners are fully engaged to oversee the process. They not only handle paperwork but also bear professional responsibility for verifying identities and document authenticity. If any documents raise doubts, require authoritative authentication (e.g., passport verification, seal authenticity checks) or direct confirmation from issuing authorities. Also consider purchasing title insurance or similar products to transfer potential ownership dispute and fraud risks to an insurer, adding an extra layer of protection.

Outlook for Systemic Reform and Investment Strategy Recommendations

Repeated large-scale frauds have prompted Japanese authorities and the industry to reconsider practices and push for reforms. On one front, the government is advancing the digitalization of property transactions. Since related digital reform legislation passed in 2021, electronic signing of real estate contracts has gradually been permitted, and online applications for property registration are being promoted. In the future, parties could use IC chip-equipped Individual Number Cards (My Number ID) for real-name authentication and electronic signatures, reducing reliance on paper documents and personal seals. This is expected to materially strengthen identity verification and reduce the success rate of document forgery. The Ministry of Justice is also exploring measures to shorten registration processing times and introduce real-time identity checks to confirm applicant authenticity at the point of filing, thereby eliminating “time lag” fraud. Some academics even propose integrating blockchain and smart-contract technologies to unify contract signing, escrow, and registration into a transparent, real-time system — once an electronic contract is executed and payment made, title transfer could be triggered automatically, leaving minimal manual gaps for swindlers to exploit.

On the other front, industry self-regulation and risk-control awareness are strengthening. After learning from past incidents, major real estate firms have tightened internal procedures: for example, high-value land transactions may require dual approval, external legal counsel may be engaged to review identity documents, and teams may proactively contact neighbors or local managers to confirm seller identity before proceeding. These additional measures increase time and cost, but are increasingly seen as essential. Some firms now offer escrow services in partnership with banks, holding funds in dedicated accounts until the transaction is verified, enabling rapid freezes or recovery in the event of fraud. While these practices are currently more common in large transactions, they are likely to spread and become industry standards.

For investors, while systemic and market improvements are underway, it is also critical to adjust investment strategy to manage risk:

First, adopt a risk-first mindset and remain cautious in the face of tempting deals. Remember that “there are no free lunches” — high returns often accompany high risks; when offers appear too good, ask “is this real?”;

Second, treat due diligence as indispensable and be willing to pay for professional services and data tools. Prevention is far preferable to regret: approach every transaction as a hypothesis that must be verified and potentially falsified;

Third, maintain liquidity and protection within your portfolio and avoid putting all capital into a single project. Diversification and insurance cannot prevent fraud entirely, but they help ensure recoverability if problems occur;

Finally, stay informed on policy changes and industry trends. As Japanese authorities tighten transaction oversight, be prepared to comply with new requirements (such as using verified bank accounts or providing additional ID). These steps may be inconvenient, but in the long run they help clean the market and protect investor capital.

Conclusion

The Osaka land swindler case reminds us that, in the face of large sums, human greed and fraudulent methods never cease evolving. Yet it also confirms that risk and opportunity always coexist in the market. For prudent investors, each high-profile scam should prompt a reassessment of internal controls. Reflecting on this case reveals a consistent core to effective prevention: transparency of information, rigorous procedures, and a calm, skeptical mindset. Only by strengthening defenses across regulation, technology, and awareness can real estate investment be made resilient to schemes and traps. Urbalytics looks forward to working with industry peers to leverage data for better risk management and to turn deep insight into secure returns. After all, for every diligent investor, the greatest return is the secure preservation of wealth and trust while pursuing profit.

References:

地面師として14億円余詐取か 会社役員が起訴内容認める https://www3.nhk.or.jp/kansai-news/20250904/2000096735.html

大阪・ミナミの不動産取引で約14億円被害 https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/799e9ff3eb3be65efd5b6f26b9d0c70fb07f5cd1

地面師とは?土地所有者を装う詐欺集団の手口と防衛手段 https://www.musashi-corporation.com/wealthhack/land-swindlers

Copyright: This article is original content by the author. Please do not reproduce, copy, or quote without permission. For usage requests, please contact the author or this site.